I’m not much of an artist, but let me tell you – my latest project is groundbreaking. I remember seeing a painting titled “Starry Night” by some Dutch artist, I don’t really remember who. It’s apparently super famous, though this confuses me. Sure, the swirls were interesting, but, in my opinion, they didn’t seem to look that much like a starry night. One night, I found myself staring up at a sky full of stars. In that moment, I came to the groundbreaking revelation that a true starry night looks… a lot like a starry night. Quickly, I snapped a photo of the sky. Next week, I will be releasing my live-action rendition of “Starry Night” on all platforms.

I was inspired to undertake this artistic masterpiece when I had the privilege of watching Disney’s most recent film “Snow White.” No, I’m not talking about the schlocky 1938 animation, which, frankly, doesn’t even look realistic. I’m referring to the 2025 remake/masterpiece, which substitutes the unrealistic hand drawn animation of the original for clearly superior digital animation – which looks infinitely more realistic.

In all seriousness, this year’s live action remake of “Snow White” has been released to middling success. In the eyes of audiences and critics, it clearly pales in quality to the original. Most of the controversy surrounding the movie, however, hasn’t been in regard to its quality but, instead, in its stated goal to modernize the original’s story. The controversy first came to prominence when Snow White’s actress Rachel Zegler said, “We absolutely wrote a ‘Snow White’ that … she’s not going to be saved by the prince, and she’s not going to be dreaming about true love; she’s going to be dreaming about becoming the leader she knows she can be and that her late father told her that she could be if she was fearless, fair, brave and true” in a 2023 interview with Variety. Zegler’s remarks sparked outrage among fans who saw the changes being made to the original story as disrespectful. When the film was released last month, these critiques were catalyzed. As Snow White’s character and the broader plot were changed significantly, these, in large part, contributed to the film’s horrendous 1.6/10 on IMDB.

The culture war inferno that had engulfed the movie obfuscates other issues with the film. The fact that this new “Snow White” emphasizes bravery, and the qualities of a good ruler is inconsequential to its actual quality. The true problem with this film, and those like it, is the underlying ideology that justifies their existence. An opinion that has yet to be purged from the culture around film – that animation is both a lower form of cinema than live action, as well as a medium for children.

The absurdity of remaking classic pieces of art into more “realistic” versions seems to have been lost on much of contemporary Hollywood, especially Disney, which has begun a slow process of pawning off its classic animated movies in the form of uninspired, vapid and cynical live-action remakes. A “live-action remake” is a trend where the story, characters and/or setting of a previous animated film is recreated to look as close to reality as possible. Usually this is accomplished through live action actors and copious use of CGI. For example, in the film “Aladdin” (2019), the titular animated character is replaced with actor Mena Massoud. In live-action movies such as “The Lion King” (2019) that have no live human characters to be replaced by actors, however, studios really have to stretch the term “live action.” Live action in “The Lion King” just entails making the computer-generated lions look more realistic than their counterparts from the original 1994 film. Usually these remakes do not make the stories they are depicting anymore realistic/grounded; “The Lion King” still has talking lions, be it 1994 or 2019. No, these remakes almost solely function on the assumption that a movie is of higher artistic quality the more realistic it looks.

While this trend is increasingly unavoidable today, the tradition of remaking animated films into live action is much older. The first major attempts at live-action remakes took place in the late 1990s with “The Jungle Book” (1994) and “101 Dalmatians” (1996). Both movies were successful, each returning well over twice their initial budget. These remakes, however, were not financially successful enough for Disney to hastily make more.

The torrent of remakes really began more than a decade later with Tim Burton’s 2010 live-action remake of the 1951 Disney classic “Alice in Wonderland.” His notably surreal rendition grossed over $1 billion dollars in the box office, making it the seventh movie ever to do so. Disney was not oblivious to the cash cow this archetype of film could become, and they began to green light more and more live-action remakes. The success of “Alice in Wonderland” continued with “Maleficent” (2014) and “Cinderella” (2015), which grossed each $800 million and $500 million, respectively. Gold was struck again in 2017 with “Beauty and the Beast,” which once again grossed over $1 billion dollars. With the massive financial incentive these movies bring, Disney has continued to put its foot on the gas.

Jump to 2025, now multiple live-action remakes are being released each year. No longer consigned to the realm of theatre, these remakes are also being broadcast straight to streaming platforms. With the slowly diminishing pool of classic animation to remake, studios have begun adapting animated films that were released much more recently. In February 2023, DreamWorks announced that it was developing a live-action remake of the 2010 animated film “How to Train Your Dragon.” Many viewers and critics saw this as an absurd turnaround, considering the original animated film was released less than a decade and a half ago.

With the usual excuse of “this classic animation needs to be modernized” left unusable, how is DreamWorks justifying this remake? In an interview with AU Direct, director Dean DeBlois responded to a question about the necessity of a “How to Train Your Dragon” remake by saying, “We could almost treat that first animated movie as though it’s the latest test screening.” It’s hard to imagine the beloved 2010 animation could be seen as something to be iterated on through real actors and more CGI. Knowing the hubris of studio executives and the industry’s disdain for animation, however, it really doesn’t surprise me that this is the excuse they would give.

DeBlois’s answer illuminates the deeper reason as to why both studios keep producing and audiences keep watching live-action remakes – they still see animation as an inferior form of cinema. Studios are advertising these remakes as not just homages or reimaginings, but as superior works. This suggests that by replacing animation with live actors, the film’s quality somehow increases. What’s concerning about this trend is how it regresses much of the last 150 years of artistic development. My comparison between Van Gogh and live-action remakes is by no means hyperbolic, early modern artists fought tooth and nail against the same dogmatic worship of realism we see in Hollywood.

Impressionism as an artistic style and movement is considered the birth of modern art, emerging in the mid to late 19th century as a response to the thematic restrictions imposed upon art by critics. In France at the time, art culture was dominated by the Académie des Beaux-Arts (Academy of Fine Arts). The Académie had strict preferences for what they would allow in their exhibitions: historical scenes, mythology and grand scenery. Most importantly, the Académie had a major preference for realism. In 1874, a group called The Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Printmakers decided to hold their own exhibition as a way for artists disenfranchised by the Académie to display their work. This first show included a wide variety of painting and artistic styles that broke from the standards of the time. These new artists were pejoratively dubbed “impressionists” by critics – a name that the movement itself would later adopt.

Impressionism and modern art contain within them one central philosophy that has molded the landscape of visual art over 150 years; art’s quality isn’t solely determined in its technical perfection or its ability to exactly replicate the subject, but instead what it evokes within the viewer. Once again, consider Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” In appearance it doesn’t really resemble a starry night, but to millions of people, it certainly evokes the feeling of wonder derived from gazing at the stars – and, while Van Gogh isn’t considered an impressionist, his painting can be described as evoking the “impression” of the subject.

Much like Van Gogh, animation often works within the same framework. The expressive color, facial features and mannerisms of animated characters aren’t meant to mimic reality but to exaggerate traits seen in real life. A great example of this would be Gaston’s walk from “Beauty and the Beast.” He strides with uncomfortably far back shoulders and a suffocatingly puffed up chest that perfectly embodies his chauvinistic character. His walk, however, would never be earnestly done by a real person, even the most boisterous chauvinist – yet, despite this irrealism, the viewer immediately picks up on the archetypal narcissism of Gaston. When animators eschew realism for expressive and impossible imagery, they are working off the same principle that impressionists arrived at in the late 19th century.

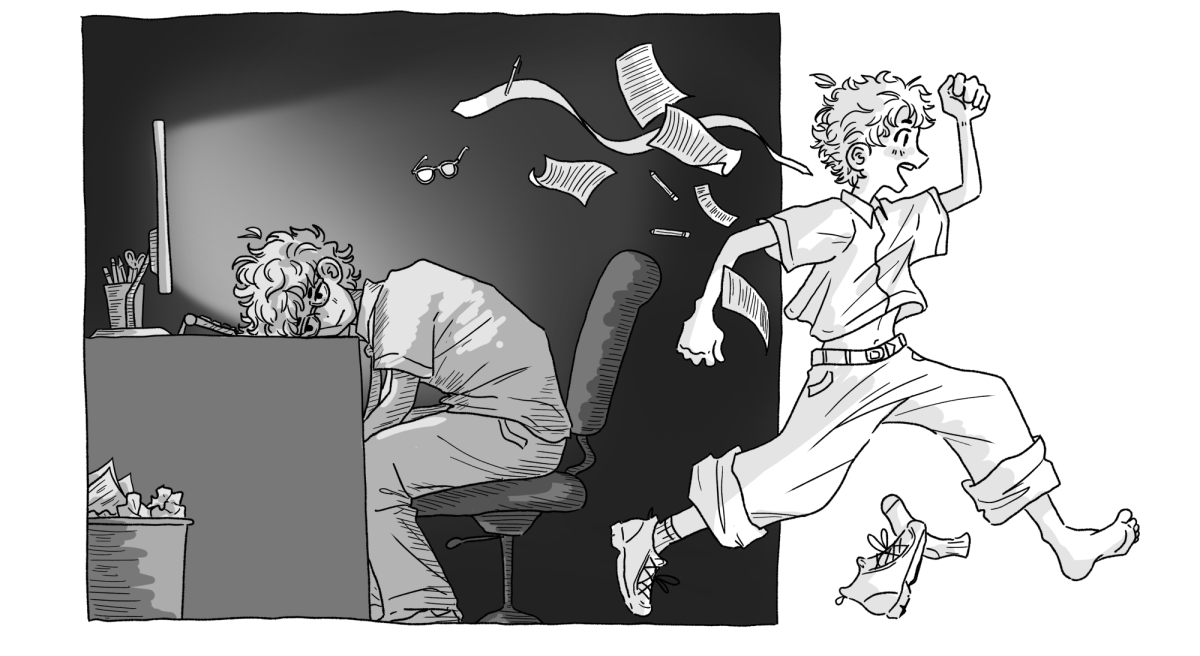

My problem with Disney’s 2025 “Snow White,” and the broader trend of live-action remakes, can be easily demonstrated. Look up Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” Now, look up a picture of someone screaming. The disparity between these two examples is the same as the one between “Snow White” (1938) and the 2025 remake.