“God, this airport is so effing sterile. I think I was just born in the wrong generation,” a young woman lamented into her iPhone as I stepped off my flight to Denver. She wore a vintage Penny Lane-style jacket, Frye Campus boots and flare jeans — an ensemble that screamed a love for the 1970s.

Initially, I found myself agreeing with her. The airport’s white floors and unsparingly fluorescent lighting felt impersonal and uninviting. I, too, yearned for warm-toned mid-century modern lamps, leather couches and patterned wallpaper that likely occupied the space fifty years ago. But then I remembered: if it were the 1970s, the early ’70s at least, this same airport likely sported vending machines selling life insurance policies for $2.50.

Young people often glamorize the 1970s for its fashion, art and music. Yet the decade was far more complex, carrying cultural highs and deeply unsettling lows.

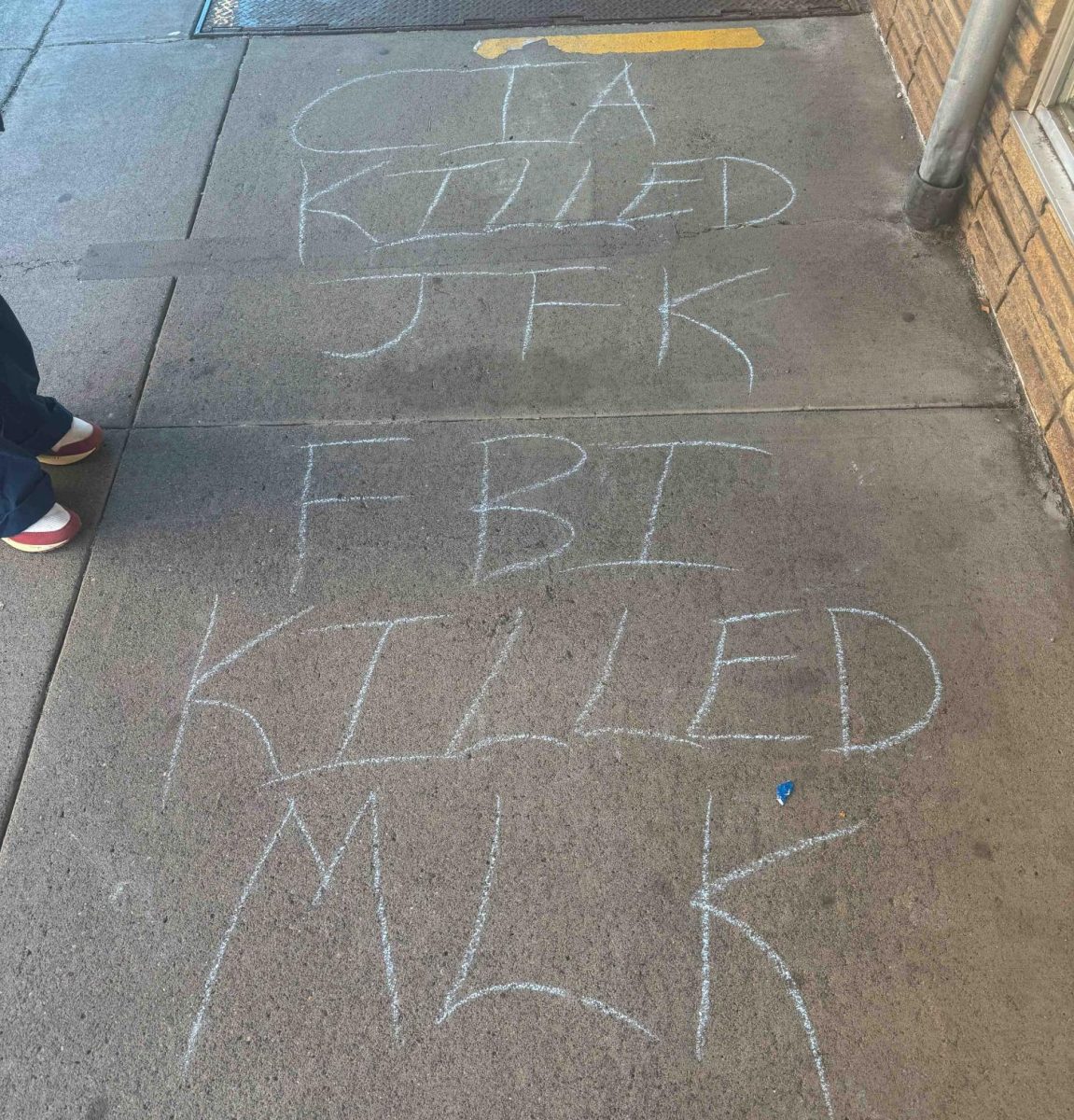

Providence Magazine describes it as, “a tumultuous and negative decade for the United States,” citing political violence, terrorist bombings and assassination attempts. Meanwhile, CNN acknowledges, “The ’70s may have been many things, but boring wasn’t one of them.”

Looking back at publications like The Whitman Pioneer (now The Wire), the contrast between the 1970s and today is stark.

The Pioneer frequently ran draft advertisements for the Vietnam War which would border Dairy Queen advertisements featuring body-shaming messages such as, “Are you skinny?… Stop over and we’ll blop you a cone, are you fat?…. Bring your friends and watch them eat!” Even progressive advocacy groups used offensive racial slurs to equate being a college student to enslavement. One article reported that “He [the sitting ASWC president] claimed to agree with the sentiments expressed in the pamphlet entitled “The Student as *N-word,*” in which a Seattle-based radical student group argued that college students are little more than groveling swine at the rough of learning; that students are an oppressed Lumpenproletariat, and that faculty and administrators are fascist reactionaries ready to stamp out the slightest trace of vitality with their “jackboots.” One comedy page from 1973, while making a more progressive stance, distastefully used sexual assault as a comedic tool by depicting a woman lying by a trashcan as a man ran away. Above her stood an older woman telling her, “Look on the bright side honey! At least it was heterosexual!”

Beyond the politically incorrect, the decade held some deeply unsettling cultural norms that should not be ignored.

The 1970s are often called the golden age of music, with artists like Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac and David Bowie shaping the soundscape. Much of this era’s musical magic, however, is intertwined with the exploitative world of groupie culture.

During the late ’60s and early ’70s, the Sunset Strip was home to a notorious nightlife scene centered around clubs like the Rainbow Bar and Grill, Whisky a Go Go and Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco. Journalist Richard Cromelin wrote in 1973 that at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco, “Once inside, everybody’s a star. If you’re not jaded, there’s something wrong. It’s good to come in very messed up on some kind of pills every once in a while, and weekend nights usually see at least one elaborate, tearful fight or breakdown. If you’re over 18 you’re over the hill.”

Led Zeppelin, a ’70s staple, was frequently involved in this scene. Music journalist Mick Farren once wrote that the band, “sat in the back of [Rodney’s] cupboard-sized discotheque getting their dicks sucked by thirteen-year-olds under the table.” Lyrics from their song “Sick Again” reference one underaged groupie, Lori Mattix with the line, “One day soon you’re gonna reach sixteen / Painted lady in the city of lies.” Another member of the band, Robert Plant, later defended the song claiming that it wasn’t about Mattix especially, rather it referred to the many young groupies the band enjoyed, which frankly does nothing to negate the disturbing reality.

The hippie movement, synonymous with peace and love, also had its sinister edges. The most infamous example is Charles Manson, whose cult-like following was rooted in counterculture ideology. His orchestrated murders performed by his following of women he groomed, including the killing of actress Sharon Tate, shocked the nation and shattered the utopian ideal of the 1960s spilling into the ’70s.

Roman Polanski, Tate’s husband and an iconic filmmaker of the decade, represents another troubling contradiction. His artistic genius is undeniable — his work in the “Silver Age of Cinema” left a permanent mark on Hollywood through cinephile-revered films like “Chinatown” and “Rosemary’s Baby.” His legacy, however, is forever tainted by his 1977 conviction for the sexual assault of a 13-year-old girl, leading him to flee the U.S. to escape sentencing.

Despite the stark darkness of the 1970s, contemporary yearning for its time is abundant not only in respect to its aesthetics, like the woman I encountered at the Denver airport, but politically considering the 77, 284, 118 American voters who voted in favor of Trump and his Make America Great Again campaign.

Nostalgia is defined as, “a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically a period or place with happy personal associations.” Most people associate nostalgia with the bittersweet memories of childhood. It serves a psychological function, providing comfort and reinforcing identity. Research shows that nostalgia can be triggered by music, scents or memories of past cultural moments, like the iconic symbols of the seventies.

National nostalgia, however, is a different beast. Defined by a collective nostalgia for a past period, a study conducted by psychologists at North Carolina State University revealed that, “Higher levels of national nostalgia predicted both positive attitudes toward President Trump and racial prejudice, though there was no evidence of such relationships with personal nostalgia.”

A recent study found that 72% of Republican and Republican-leaning individuals believe America was better off 50 years ago. The very phrase “Make America Great Again” is rooted in a nostalgia that, when interrogated, potentially intentionally overlooks, the racial, gender and economic inequalities of past decades.

This yearning for the past is bizarre. Los Angeles Times reporter Jonah Goldberg argues that as “Americans are richer today than decades ago.” In addition to wealth, Goldberg also cites the fact that “We live longer, have more free time and travel more affordably. Infant mortality has been cut in half; our air and water quality is vastly improved. Our cars are much better and much safer. Our homes are bigger and more comfortable.” And of course, “We’ve made real progress against racism in the last several decades.”

With all of this in mind, why in the world do so many Americans want to “Make America Great Again”?

The North Carolina State University study discusses this phenomenon in the study’s introduction where they cite something called “intergroup threat theory.”

“The intergroup threat theory (Stephan et al., 1999) posits that intergroup prejudice and hostility is largely explained by perceptions of threats to one’s ingroup by an outgroup. In line with this theory, substantial evidence has found that intergroup prejudice is strongly influenced by both realistic and symbolic threat perception (Stephan et al., 2002; Mutz, 2018).” Realistic threats refer to, as the name implies, legitimate risks to one’s well-being such as economic livelihood, physical safety and political power. The symbolic threats refer to more abstract threats such as changing cultural norms and dismantling tradition.

The introduction continues emphasizing that, “when a marginalized minority grows in political, economic or representative power, realistic and symbolic threats can be conflated.”

Trump’s weaponization of national nostalgia makes perfect sense. After all, if his supporters truly yearned for the United States in the 1970s, his laundry list of sexual assault allegations, including some against minors, would likely be dismissed. This would be similar to how Led Zeppelin and David Bowie remained popular and lionized despite their behavior.

Furthermore, Trump has channeled a sense of national nostalgia so strong that particular demographics yearn for a time when they lacked substantial rights in the United States. Black Americans and Latinx-American support for Trump soared in the 2024 election.

The 1970s were an undeniably transformative decade, with cultural milestones and social upheaval. When we reminisce, however, it’s essential to acknowledge its full spectrum — not just its aesthetic appeal.

Nostalgia, when wielded without critical thought, becomes a dangerous weapon. It can blind us to the real progress we’ve made and romanticize an era that, for most, was anything but glamorous. I think it’s safe to say that we were born in the right generation, but give me four years and that might change.