“Hey baby girl, let me see that ass.”

I started, nearly letting the stack of books I had been carrying slip from my grasp. A man leaned against a wall on the sidewalk in front of me, lazily flicking the ash from his cigarette as he slowly let his eyes graze over the length of my body. I felt the sour taste of bile rise up in my throat.

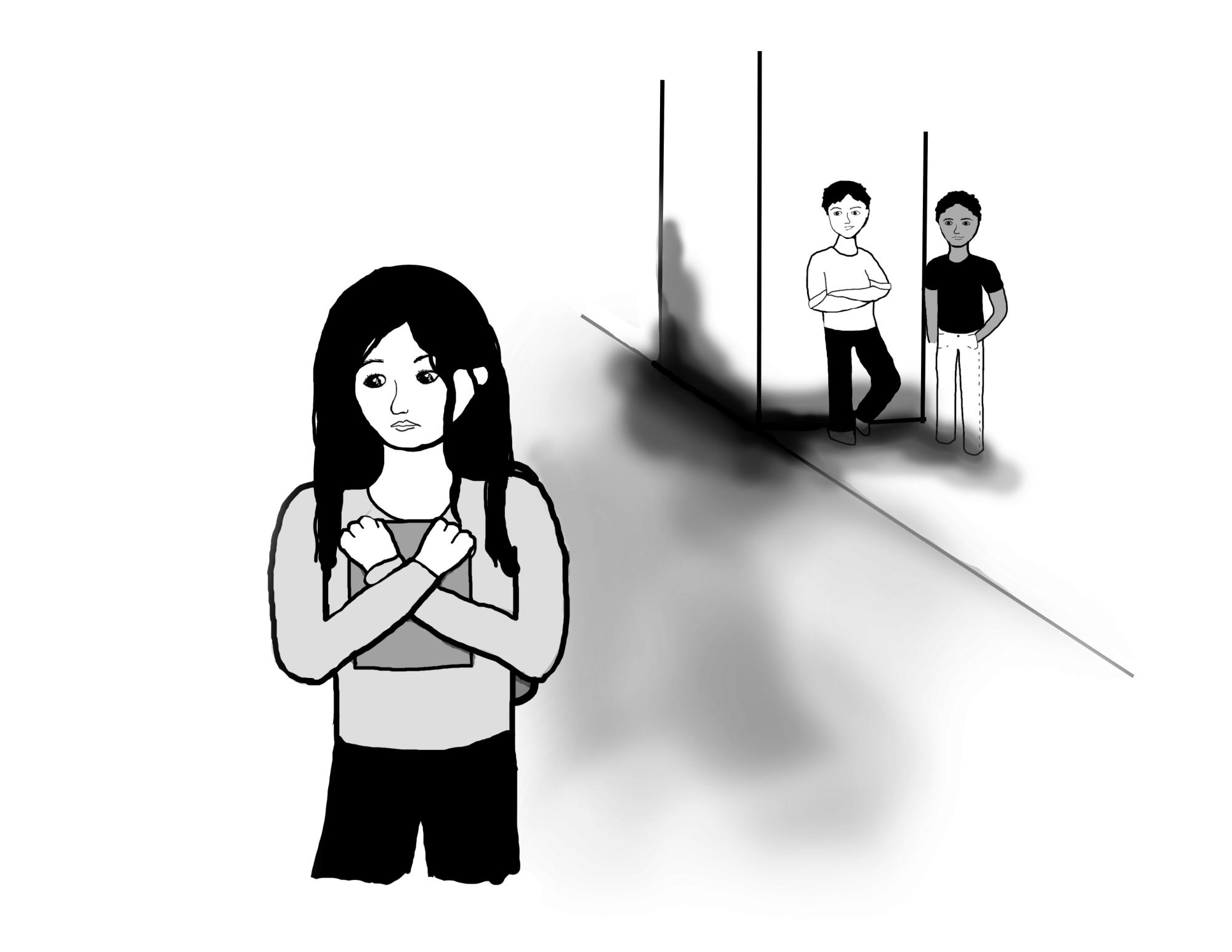

It was nothing I hadn’t experienced before, but the onslaught of emotions that follows in these situations never fails to unsettle me. Panic flooded my veins, my heart beat tumultuously, the flush of anger and humiliation crept up my neck and across my cheeks.

For most women I know, it is a truth universally acknowledged that experiencing verbal harassment on the street is a fact of nature, an inevitable truth that we learn to expect and live with. And so, like every other time when a leering man confronted me on my walk from campus to my apartment, I kept my eyes on the ground and continued walking.

Right To Be (RTB), a nonprofit organization that offers online resources and support for victims of street harassment, defines street harassment as “an interaction in a public space that makes you feel sexualized, intimidated, embarrassed, objectified, violated, attacked or unsafe.”

Examples of street harassment include comments that are sexually explicit, racist, homophobic or derogatory in any way. Street harassment can also come in the form of leering, making vulgar gestures, exposing oneself to someone, sexual touching or grabbing, whistling, barking or growling noises.

Sadly, nothing about street harassment is unusual. The initial paralysis, the sudden and instinctual move to protect oneself, the humiliation and anger, even the tendency to turn the blame inwards. It is something that all women experience in their everyday lives. In fact, junior Meredith Luce says she would find it surprising if a woman managed to graduate college without being exposed to a litany of such incidents.

“I think it’s unusual to get through college without having any sort of negative experiences and being exposed to [verbal and sexual harassment] or having friends who have gone through that,” Luce said.

According to the journal Violence Against Women, 77% of women have experienced street harassment in the United States, which can result in harmful side effects on victims, such as a reduced sense of safety, anxiety, depression and refusal to engage in civic life.

Sophomore Cleopatra Nabyonga also describes her initial reaction when being street harassed as one of shock and paralysis.

“You feel incapable of doing anything,” Nabyonga said. “You feel stuck, like you’ve been put in a shock zone or the fight-or-flight mode. Where it’s like, how do I respond? Do I run from this situation? Do I react? I think that’s always something that I grapple with – do I [choose to] respond in anger or do I [choose to] respond in fear, and what would happen?”

So, what do you do if you are a victim of street harassment?

According to RTB, there is no “right” or “perfect” way to respond to street harassment, but the organization recommends trusting your gut and listening to your instincts. For those who prefer more direction, RTB offers a list of step by step instructions for responding to street harassment.

“It’s okay to do nothing,” a guide on the RTB website states. “It’s okay to flip them off. It’s even okay to smile and keep walking. You get to decide what’s best for you.”

In an email to The Wire, junior Megan Wick described her approach to dealing with street harassment. Although she utilizes certain tools like headphones, she still keenly feels the possibility for danger in such situations.

“I often walk with headphones in, even if there is no music playing, just to dissuade any sort of catcalling if I’m walking alone,” Wick said. “At least if it does happen, I can pretend I didn’t hear it and not respond. Otherwise, I ignore it and walk faster away from the perpetrator, because I worry that if I respond negatively I’ll be put in a dangerous situation.”

According to RTB, your top priority is always your safety. But if you do feel safe enough to respond in the moment, experts from RTB recommend reclaiming your space by setting a boundary. Looking the harasser in the eye and denouncing their behavior in a strong, clear voice functions not only to reclaim your space, but also your autonomy. While this can help individuals feel like they can respond to the situation, it is never a good idea to engage in a back-and-forth argument with the harasser.

Engaging in further interaction with one’s harasser will always run the risk of escalation to physical violence. Examples of these instances are not difficult to find. Just last month, two young women were stabbed in a Brooklyn, New York deli after refusing unwanted sexual advances from a man. In a society that is hyperfocused on the sexualization of women, it is sadly not surprising that objectifying women and inciting violence against them has become the norm.

A man may objectify a woman by ascribing her worth to her physical appearance or sexual desirability. Verbal expressions of sexual aggression can contain multiple messages, but they all point to the subordination of women for the purpose of catering to the male gaze. By making a sexually perverted comment to a woman, a man succeeds in objectifying her, as he places the entirety of her value on her ability to please him sexually.

Sexual objectification and power struggles are pervasive phenomena. In an email to The Wire, Junior Bella Nasman emphasized how women in our society have internalized gender narratives that are centered around pleasing the male gaze.

“Women have literally been trained to view our bodies through a third person lens and men are socialized to view women as objects of consumption,” Nasman said.

Women are all too familiar with these demeaning interactions. The twisted comments may sound like a compliment to a bystander, but they are charged with sexual aggression and speak to the culture of misogyny that we live in.

“[Sexual harassment] is framed in a complimentary way,” Luce said. “But that doesn’t mean it feels like a compliment. It feels gross. It feels like you’ve been in some way commodified.”

Many women struggle with this aspect of feeling objectified in these situations. And that is the point. Perpetrators of street harassment feed off this and use it as a means to empower themselves.

Wick described how street harassment makes her feel powerless.

“I instantly feel either scared or ashamed, wondering what it is that has drawn attention to me (my outfit, my body, my walk, etc). I’ve experienced catcalling since I was a preteen, around 11 or 12, and I still feel a bit like that same young, small girl when it happens to me,” Wick said.

The effects of catcalling can linger long after the incident itself. Nabyonga expressed how street harassment affects her, even hours after the incident.

“Not only does it create that sense of feeling mad and angry,” Nabyonga said, “but it also becomes internalized. A lot of times I’ll sit and reflect and say, maybe it was the way I was wearing or maybe it was something that I was doing, but then I have to remind myself that it has nothing to do with what I was doing or how I dress.”

Although many women experience similar responses to street harassment, there are also variations. For instance, as a woman of color, the street harassment Nabyonga has experienced often contains a racial dimension. Due to derogatory racial stereotypes, she is hesitant to allow herself to express her anger, a very normal and expected feeling associated with being the recipient of street harassment.

“When I am catcalled,” Nabyonga said, “[I don’t] want to play into the ‘angry Black girl’ trope, but I do get angry. I feel as if I’m being devalued. I feel as if I am being objectified. I usually grapple between that sadness and anger. And I think this is an experience that a lot of women share.”

Nabyonga has also noticed a pattern of racially charged fetishization through her experiences with street harassment, in which her race as well as gender is made into a commodity for men.

“I think as a Black woman, I’ve become a test experiment for people to say, ‘Hey, I’ve never been with a Black girl before,’” Nabyonga said.

Luce has observed patterns of sexually derogatory narratives even in predominantly female spaces. While attending an all girls school, Luce recalls hearing many of the same sexually demeaning comments that she was most accustomed to observing in mixed gender spaces.

“I was so struck by how a lot of the language and narratives I had become really familiarized with within male circles were being related and reproduced in female spaces,” Luce said.

She theorizes that this has something to do with the pervasive culture of complacency that we are exposed to. As women hear and become accustomed to hearing sexually dehumanizing messages about women, they begin to unconsciously adopt and internalize those narratives themselves.

The narratives and beliefs that we have created around street harassment are also a result of our culture of complacency. We have become so used to being sexually harassed that we have accepted it as an expected aspect of our everyday lives. Survival seems to hinge on developing a constant, instinctual self-awareness of our surroundings.

“I do think a lot of awareness about it comes with experience,” Luce said. “It sucks that that’s the way that it is [but] there are definitely spaces that I avoid. I think social awareness and self-awareness are super key if you’re by yourself.”

Luce utilized these skills of self and social awareness while working a summer job in Chicago, especially when it came to experiencing the night life. Recalling all the unwanted comments and advances that she and her friends regularly experienced from men, Luce described how local women took their comfort and safety into their own hands, developing a garment dubbed the ‘Subway Shirt’ to avoid sexual harassment on mass transit. Aware that their physical presentation poses a potential liability to their own safety, women have resorted to adapted ways in which they can circumvent any sexual harassment and go about their daily lives.

But are there ways to fight street harassment that does not place the responsibility and effort solely on women?

There are many organizations like RTB that emphasize the potential for bystanders to play a significant role in stopping street harassment. However, in an interview with SBS News, Dr. Bianca Fileborn, senior lecturer in Criminology at the University of Melbourne, acknowledged that while bystander intervention can indeed play an important role in stopping sexual harassment, more needs to be done to address the root causes of the problem.

“Ultimately, we need to be targeting the behaviors and the actions of men who are engaging in these behaviors and challenging those social attitudes and norms that normalize and excuse street harassment in the first place,” Fileborn said.

Junior Cate Culligan has similar thoughts, particularly when it applies to challenging these harmful behaviors that have become deeply entrenched societal norms.

“I think it would start by educating people on what behaviors are wrong and showing why they are harmful and hurtful,” Culligan said. “It is really important to emphasize that harassment is a learned behavior that escalates over time, and so it is important to catch and have consequences for [instances of verbal harassment] before they progress into something worse.”

Nabyonga also emphasized the importance of conversation.

“Communication is so necessary and so key. We’re always communicating, whether it’s verbal or physical. This is, I think, one of the biggest things that would really help. Having these conversations and allowing people not to feel like they’re alone,” Nabyonga said.

Whether you choose to ignore the perpetrator, seek help from a bystander or holler back, know that there are options to fighting and coping with street harassment. Conversations and education can go a long way in creating a safer future, and you are not alone. Despite being unfortunately common, there are ways to combat street harassment and reclaim autonomy and power in the face of objectification.