We’re all deeply immersed in Whitman. Our majors can shape our core friend groups, we develop favorite study spots, whether it be in the Science Building amidst the greenery or an individual desk in the Penrose, and we schedule our lives around assignments and on-campus obligations.

Part of the reason why this immersion is so deep is because it didn’t just start at Whitman; we spent a significant portion of high school thinking, fretting and dreaming about college. After spending so much time thinking about academics, many of us find ourselves wondering how we can make the most of our college education.

Despite a shared identity as Whitman students, we come from different academic backgrounds, have different goals and think about the world in different ways. For some, highly-structured education might work better than the self-driven learning that Whitman provides. For others, though, Whitman’s liberal arts model is the key to their success; a less-structured education can feel freeing and encourage deeper engagement.

Understanding how we work within different academic models is complicated enough in college, and even more so in high school as we apply to schools. Choosing a college isn’t just about location, tuition, prestige or parental expectations – there’s also the question of learning environment. Different schools subscribe to different philosophies of education, and what structure works for an individual is integral in their compatibility with a college.

Senior Reya Fore had a different schooling experience than the average American teenager, and her background demonstrates several types of education models.

“I went to K-12 Montessori school, did two years of normal public high school [and] full time running start for my last two years of high school,” Fore said.

Fore continued to speak about how large the shifts have been between different phases of her academic career. Each segment of her education had a different vibe, whether it be in terms of difficulty, student engagement or room for student choice.

Sophomore Pearl McCulloch entered Whitman from a different place than Fore, although her background also deviates from the stereotypical high school experience. In fact, she had already been preparing for her major for years before Whitman.

“I kind of knew that I wanted to be a vet at an early age,” she said. “My high school had different academies that different people would go into … so there was health, race policy law, fashion and design, computer engineering. I was in the health academy,” McCulloch said.

In her health track, McCulloch learned about her future career path, from things such as email etiquette to an internship at a local hospital. Her education was specialized and came with its own set of career-specific curriculum.

I also went to an alternative middle and high school – an arts-focused public school – and graduated with a double honors in the Theatre Performance and Creative Writing pathways. While the curriculum and environment at my school were different from the typical American high school, the public school system still funded it, just like in McCulloch’s and Fore’s experiences.

Out of the people I talked to, the most traditional education happened in a private school. Senior Charlotte Flannery attended an all-girls’ Catholic school for 14 years and described the environment as a “Catholic bubble.” A big part of her education seemed to be focused on discipline.

“I think I still have a lot of those … not tendencies, but muscle memory from Catholic school of the guilt of showing up late to class or not turning something in on time, those little things. I feel like educationally that’s still ingrained in me,” Flannery said.

Whether or not a school is religious, schooling in general tends to instill specific structures: Fore’s Montessori education encouraged experience-based learning, McCullough’s school helped students specialize early, while Flannery’s school was much more structured and curriculum-based.

Our high school experiences can be influential in what college we choose to attend. For example, when Flannery was first applying to college, it seemed natural to continue her Catholic schooling.

“I feel like most Catholic high schools are like this, but I guess I can only speak to mine. It tried to funnel you into the Catholic universities,” she said.

Flannery took a gap year, then went to Fordham University in New York City for her freshman year and realized quickly that it wasn’t the right fit.

“I wanted something new. And I felt like in my gap year, I started to have my own identity and opinions about my education, and wanting to really take that into my own hands,” Flannery said.

A big problem she had with Fordham was the students’ lack of interest. “It wasn’t like they necessarily wanted to be there. It was just like the next step. It was like their parents said, okay, you’re going to college and it was a Catholic school. It was in a city. So why not?” said Flannery.

While Flannery feels that Whitman’s academic expectations for its students are less rigorous than the ones she had in Catholic schools, Flannery appreciates Whitman’s “free-flowing” nature, as it allows people to pursue the things they’re truly passionate about. She says that people in her classes at Whitman are much more engaged than at Fordham, and a big part of that has to do with the way each school approaches education.

McCulloch also appreciates the shift she felt in engagement from high school to college.

“I always assumed it was kind of like a universal high school experience that people don’t want to be there. So, you know, even in senior year when you think people would have matured a little bit, you’d have people just acting up in class and you’d be sitting next to that table of people just being disruptive,” she said. “[Here], people genuinely want to attend their classes. You can skip class, but you know that you’re sacrificing yourself, not getting a call home to your parents or anything.”

Fore feels engaged by the way Whitman lets her explore many subjects and doesn’t expect perfection.

“The truly interdisciplinary learning that I experience at Whitman reminds me a lot of my experience in the Montessori classroom,” Fore said. “If I want to pour myself into my studies I can, but I never feel overwhelmed with busywork and pointless tasks like I did in my two years of traditional high school.”

She said that Whitman’s liberal arts curriculum was a big draw for her because she didn’t want to be forced to stick to one field of study.

It’s important to note that the interdisciplinary requirements at Whitman aren’t a positive experience for everyone, despite being a core aspect of the liberal arts education model and therefore the Whitman academic culture.

One interviewee, who requested anonymity because they didn’t want their name attached to critiques of the college, expressed frustration at the distribution system.

“Hot take, distribution requirements that don’t have to do with your major, you should have the option to pass/fail … My drama class, if all I had to do is read plays every week and then come in and discuss the plays and not have to write about them, I would be delighted,” they said.

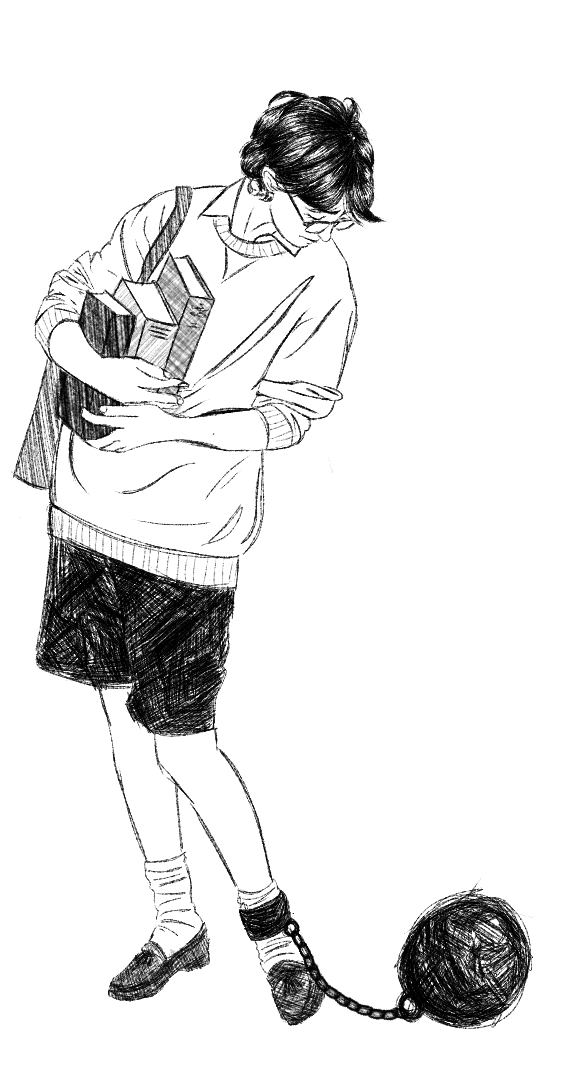

However, with the current distribution structure, this interviewee feels unable to fully commit to their drama class because they’re more worried about passing classes for their major. They “appreciate that Whitman wants us to be well-rounded” and that they have enjoyed and learned from some of their distribution classes, but ultimately, it feels like an added stressor at a school that otherwise gives students a lot of freedom to self-direct their education.

Whitman’s academic model can also create an element of disparity between humanities and STEM majors. As a humanities major who is decent at math and science, I haven’t had much trouble in my science and quantitative analysis requirements because Whitman has made an effort to create a whole section of “STEM classes for non-STEM majors.”

In contrast, Whitman doesn’t offer many humanities courses for non-humanities majors – if you’re taking a humanities class at Whitman, there’s an expectation that you will do dozens of pages of readings a week, participate in class discussions and write in-depth analytical essays.

During our conversation, I found myself agreeing with them. I took a class about the physics of music where the professor recognized that students were registered just to fulfill distribution requirements. That same kind of conversation isn’t necessarily had in entry-level humanities courses that STEM-oriented students are taking to fulfill requirements.

For STEM majors who don’t click with readings and discussions, Whitman’s distribution requirements can put them in a tough spot. It’s no secret that the humanities tend to be considered ‘less challenging’ than math and science, but in reality, the two can be equally difficult for different types of brains. For someone with a more quantitative brain, dissecting a poem line-by-line might feel as difficult and stressful as dissecting a frog would be for me. Writing an essay is time-consuming, difficult work.

I find that even for me, someone who writes for fun, I enjoy my humanities classes more when there are several different ways that I can show my engagement, and my professors understand that not everyone learns in the same way. Whitman has a reputation for being a school for self-directed learners and people who want to choose their own educational path, whether it be in the form of Individually Planned Majors or flexibility in research project and essay topics. While one of the tenets of a liberal arts education is interdisciplinary studies, not every student will learn disciplines at the same pace.

It might seem like there’s a simple solution: people who only want to focus on their major should just go to a school where they can do that. But the environment at Whitman isn’t available at every school. For example, even though I didn’t ask about professors, interviewees gushed about Whitman faculty.

“Professors have consistently given me their time and assistance whenever I needed it,” Fore said.

Not only are professors available, but they also look after their students. “Professors really care about you … professors want you to succeed and they want to work with you,” Flannery said.

The resounding appreciation of professors speaks to one aspect of Whitman’s academic culture. However, this is not the case at every school. People of all majors, backgrounds and learning styles deserve to have that sort of support if they want it. That’s why it’s not as simple as transferring to a different college where there are less distribution requirements. The small community and inclusive culture at Whitman are huge draws for all kinds of people.

But like it or not, school shapes who we are and who we grow into. It occupies most of our childhoods and, for a significant part of the population, our young adult lives as well.

Our lives within academics are more than just daily classes and homework. Our middle and high school experiences shape our approaches to academics and our personal goals and skills contribute to our preferences.

The ways in which we experience Whitman will differ, but we can make the most of our time here by identifying the aspects of Whitman’s academic culture that speak to us the most.

Whether you’re a freshman or a senior, reflecting on your education can provide fascinating insights and help you develop a deeper understanding of yourself. Don’t be afraid to advocate for yourself and make the most of the parts of the Whitman experience that do work for you. While our past experiences, goals and personalities influence our satisfaction with our learning environment, we are by no means passive within it; find out what works for you, and embrace it.

Mary • Dec 7, 2023 at 1:02 pm

Excellent and insightful article. As the parent of a current student as well as an applicant for the class of 2028, I appreciated that this article addressed several questions my applicant had. In addition, this served as a wonderful peek inside the academic culture at Whitman. Thank you for covering this topic!