On the decline: investigating greek life at Whitman

April 27, 2023

Editor’s note: We as editorial leadership erroneously removed an aspect of the piece, which we have now corrected.

After Whitman College’s external review of Greek life returned an extensive list of recommended improvements and noted the presence of students “who were adamant that Greek life should be abolished at Whitman,” the College’s purported commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion was put to the test. While Whitman decided against total abolition of Greek life, one year after the release of the review, the inequities which prompted it in the first place have yet to be resolved.

In response to the review’s recommendations, Whitman’s administration hired a new Associate Director of Student Activities: Sorority and Fraternity Life (SFL) and Student Leadership, Stace Sievert. A New Mexico State and University of Mississippi graduate and Zeta Tau Alpha alumna, Sievert oversees and coordinates Greek life on campus. Sievert functions as a sort of middle-man between students and the administration.

While Sievert provides communication and organizational help for SFL student leaders, she admits that the transition period has been intense.

“There’s been no one really in my chair for two years,” Sievert said.

The disorganization that Sievert inherited is the result of multiple structural issues, which predate both her arrival on campus and the current batch of student leadership.

From the moment of their inception, fraternities (and, later, sororities) had an inescapable dividing presence on university campuses. In 1836, at the very start of what would go on to become one of the largest, wealthiest organized groups in America, college presidents across the country called the budding groups “un-American”: they were a tool for young rich white men to separate themselves from their “less desirable” classmates.

The patriarchal, exclusive culture bred by fraternities has long since become a norm on college campuses. As author and Tulane University Professor Lisa Wade writes, the proof of this toxic cultural norm “is in the knee-jerk insistence that they are too formidable to fight.”

Sororities at Whitman are perhaps the most impacted by this legacy of misogyny, with the most glaring example of this being sororities’ reliance on on-campus residence halls for housing.

Prentiss Hall is home to every on-campus sorority, in addition to housing non-affiliated students. Specific areas in Prentiss are dedicated to individual sororities. All sections have lounges and chapter rooms, but due to declining interest and member retention, the sororities often have non-pledges living in their sections – something fraternities don’t have to deal with. Even the administration seems to be unable to deal with the problems on-campus sororities pose.

The Wire was invited to attend a Greek leaders meeting, where Sievert had organized a Narcan training. At the training, boxes of Narcan were distributed, alongside signs with arrows to help identify the Narcan storage location.

Sorority leaders immediately identified a problem.

“We don’t really have a space that I think would be good [for Narcan storage]” said one of the sorority presidents, who explained that it would more than likely go missing in a shared environment like Prentiss and that they would have to remove the Narcan frequently to bring it with them to events – as they are unable to host their own.

Sievert did not have a solution for the sororities – advising them to “put it near” the section’s fire extinguisher.

President of Kappa Kappa Gamma and sophomore Ainslee Newman says that there are few, if any, adequate spaces for the sororities both on and off campus.

“It is very gendered,” Newman said. “What’s the point of being in a sorority if you don’t have your own place and your own space?”

While the community aspects of sororities are one of the main attractions for prospective pledges, these aspects of sorority life at Whitman are largely relegated to fraternity houses.

When planning parties, “the fraternities are where we usually turn to,” Newman said.

For Newman, the social dynamics at these parties, hosted in an unfamiliar, male-dominated space, reinforce misogynistic power structures.

“They’re the ones who have the rules and the power about what we can do,” Newman said.

Because of this, according to Newman, “people normally consider the sorority parties as just another Beta or Sig party, even though we’re the ones organizing the whole thing.”

The gender-based inequity was briefly acknowledged by the external review, though they write that, “Fraternities and sororities are both privileged enough to have space on campus, which did not seem to be afforded to most student organizations on Whitman’s campus.”

Sievert echoes this belief, “do I think it’s a problem that they’re different? No.”

Sievert’s assertion that “the sororities don’t recognize what a sweet deal they have in Prentiss” is disheartening to sorority leaders, who have been blowing the whistle on this inequality for years.

An anonymous sorority leader believes Sievert’s assertion is unfair.

“It’s not that we don’t realize how good it is,” they said. “It’s that equitably we deserve more than that.”

Sororities’ symbiotic relationship with fraternities means that, even if they were to receive perfectly equal treatment, they would still be complicit in the problematic culture of Greek life itself.

The Greek system has big pockets, with fraternities owning about three billion dollars worth of real estate across 800 American campuses.

Fraternities and sororities have their own exclusive rituals and initiation processes. They can have “closed,” exclusive parties. As an organization, they can dodge accountability when it matters most.

While student members of sororities and fraternities at Whitman staunchly defend their participation in the tradition, the exclusive nature of the groups is fundamentally antithetical to the College’s inclusive mission.

As such, any DEI efforts from student leaders and administrators are bound to fall short – precisely because they are cementing institutional structures that are exclusive by the very fact of their existence.

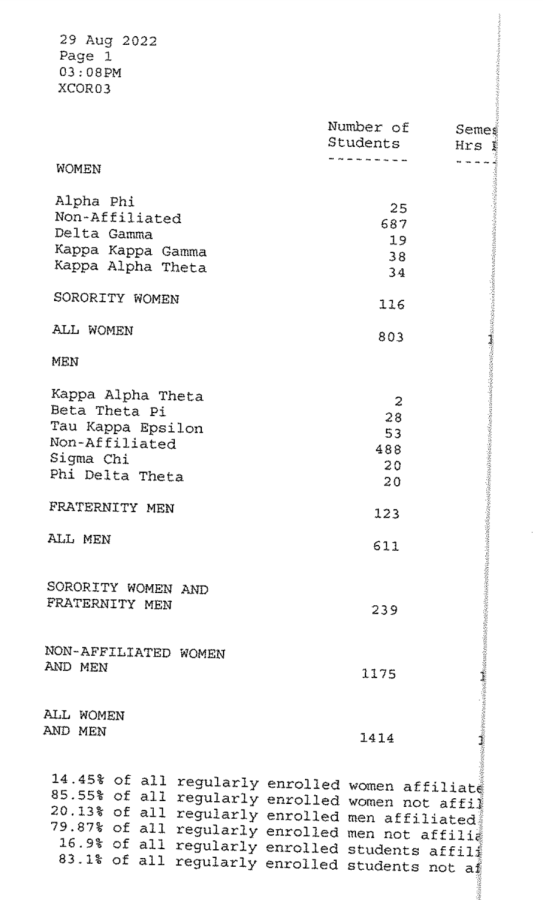

This was rendered obvious when, in the Spring 2022 report card, Kappa Alpha Theta was listed twice: first as having 34 “women” sorority members, and then again as having two “men”; singling out Kappa Alpha Theta’s two trans members and forcing them into an offensive label.

In an internal email obtained by The Wire, Sievert presented the President of the sorority with two choices for how to move forward: “I can take a sharpie and black out the row for [the sorority] under “men,” wrote Sievert.

The second option, however, was to “distribute it as it is.”

“The advantage of this is that the report looks clean, and doesn’t have a weird black sharpie line across it.”

The unnamed sorority leader remembers having conversations with the impacted sorority when the report was released. She reported that Sievert was initially opposed to blacking out the discriminatory row.

However, in an interview with The Wire, Sievert remained firm that the decision to black out the error was entirely hers.

The anonymous sorority leader recalls feeling like they weren’t being listened to during the back-and-forth between leadership and Sievert.

“No one cares if it looks messy, it shouldn’t be there,” they said.

An anonymous sorority member told The Wire that this is “a reoccurring issue.”

“Specifically administrators release stuff like this.” They said this is something they’ve experienced “over the years as a member of Theta.”

The anonymous source said that they are “thankful for my sisters for pushing against this in particular when it occurred,” though they expressed general frustrations with the way discriminatory errors are handled.

“It’s difficult trying to push against something as unfeeling as Whitman and the sorority administration.” Sievert admitted that this is her first time working at an institution with trans SFL members: “This is a first for me. But, I knew when I saw it that it wasn’t acceptable, and I tried really hard to make it right. I’ll take the heat for having not.”

The immediacy of the administrator’s concerns over widespread knowledge of this document’s existence was not reflected in Stace’s initial suggestion to Kappa Alpha Theta leadership to have a report that “doesn’t have a weird black Sharpie line across it.”

Ultimately the error was fixed, which Sievert credits to Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion Dr. John Johnson, who got involved after students brought their concerns to him.

Johnson told The Wire that he believed it was his “moral, ethical and professional responsibility to help resolve that issue.”

“What happened was wrong, could not and should not happen again and seemed to be the result of structural failures that I was in a position to help address,” Johnson said.

While Johnson finds the question of Greek life’s detriment to DEI issues “subjective and largely about execution more than existence,” he notes that “a progressive decline in the number of students involved with Greek life” at Whitman “speaks volumes.”

As both the Narcan training and report card show, even the most basic attempts at addressing the structural issues of Greek life end up reinforcing the problems.

After a year of implementation, it seems the external review was only able to place administrative bandaids on structural wounds. According to Johnson, “there’s no viability without diversity, equity and inclusion.”

Marta • May 15, 2023 at 7:34 pm

For a Whitman student to point out the exclusivity of a single campus group is…puzzling.

Colleges and Universities are inherently exclusive, sports teams which require access to expensive equipment and years of coaching are inherently exclusive. Access via airplane or private vehicle to a campus in a small town is inherently exclusive. Why single out the Greek system? As described in an earlier Wire article, student engagement in general is low. I’d be interested to hear how other groups across campus are coping with this issue, and maybe some positive strategies could reach any student who’s feeling disconnected. Community connection is one of the best parts about Whittie life, I hope students find their way back together again.

Whitman parent • Apr 27, 2023 at 6:33 pm

Parent here. The whole Greek system is anti-inclusion. It’s about creating an in-group or joining one. Yes, there are Greek groups that encourage community service, but still – they’re their own groups. Not what we should be encouraging folks to do.

Another parent • Apr 28, 2023 at 4:39 pm

Another parent (and alum) chiming in – given the low numbers of student members of greek life why are College resources being allocated to resolving issues with the fraternities and sororities, particularly given the damning report about the current status of greek life at Whitman? I think the fraternities’ and sororities’ national organizations should foot half of the bill for the Associate Director of Student Activities position. The FTE is not needed for the independent students – a significant majority of student enrollment. I do not see the value of fraternities and sororities at Whitman.

anon • Apr 27, 2023 at 5:34 pm

Thank you for publishing what you were able to publish! Good to see someone on campus who is willing to openly expose the administration’s consistently abusive behavior at their own risk. I personally think Greek life should exist, but your structural critique of the Greek system is nonetheless appreciated.

NA • Apr 27, 2023 at 12:59 pm

Hmm not members of Greek life being lied about the purpose of the article so the writer could get quotes ti take out if context. Loving the “journalistic integrity”

Clover Beaty • Apr 27, 2023 at 12:04 pm

As the only trans member of Theta, think it’s obvious I was quoted, but oh well. I still stand by the love and family I’ve been given by theta and how much I love my sisters. Admin’s the one who perpetuates several issues and honestly? I doubt it’s going to change no matter how much they’ve been called out. They have comfortable positions with a lack of change leaving them to enjoy comforts which could be risked if they push for change. It’s a cycle I hate and wish was erased for something that actually cares about sorority members on campus.

-Clover Beaty

Colleen B • Aug 31, 2023 at 2:09 am

As a trans member before you in theta (so proud of you btw, much theta love), I was admittedly nervous being who I was but my story is very similar to yours. The fact that I was trans (and note hadn’t gone through any of the medical transitioning things) NEVER came up during my process of becoming a full member of Theta. Every single member of theta, and later on a number of alumna too when they found out, reached out in support of me to assure me that I deserved to be in the position I was in. There was nothing but love and support, even now from the broader theta world.

Truthfully me being 6ft 3in was the bigger issue (pun intended) as some of the ceilings and doorways in Prentiss are pretty low.

Soroities being in dorms is not a “sweet deal” when formals can’t be held in our own space. The amphitheater is not exactly a secure space, and if one needs to rent a space there is significant added cost/safety measures that need to be put into place. In addition, when you aren’t living in Prentiss you couldn’t just go hang out in the lounge or visit sisters. You’d have to have someone open the door every time, which I guarantee is not something the men have to worry about. This poses a problem especially during chapter, where basically someone has to be there to let folks in.

Also given this is my first time hearing about the trans members being listed as men in an official report, and the suggestion being to “sharpie it out” quite frankly makes me mad. How can an organization with 250,000 thousand members and over 140 chapters look at a transwoman and think “ok yep woman gotcha putting you down as such” with no issue but Whitman thinks that using a sharpie is an adequate measure? Whitman come on you can do way better than that. It shouldn’t even have been an issue. I’m not surprised that the fellow theta sisters were the ones to push for the change, which demonstrates a lot.

I agree that Greek Life is structurally problematic when it comes to DEI (with changes that need to be made), but, and possibility showing my own acknowledged bias, I do feel there is a place for it with changes, given how accepted I was and am as a transwoman, despite not doing the somewhat expected medical stuff. I have pride in my sisters, and feel that losing these spaces would have a much higher impact on women vs. the men, who could just disaffiliate from the college as at least some of them own their own houses. Unless a major bit of funding comes in to buy a sorority house, it’s not something that could be easily done for the women.

BTW Clover know that as a sister, I’m proud that you became a Theta.

-Colleen, ’19 Alumna

Current (Tall) Whittie • Sep 14, 2023 at 11:02 am

Hi! Thank you both for commenting and detailing your experiences. It definitely helped humanize the story. Colleen, in particular, I wanted to thank you for pointing out the issue with height in Prentiss! I’m a pretty tall (6 foot) cis woman who lived in Prentiss my freshman year and while I knew from my own experiences that it isn’t a great place for tall people, I didn’t even consider the problems that might cause for trans women. Again, I’m only 6 foot, but my feet would hit the edge of my bed since it’s the only hall with normal twin beds, I’d have to tilt the shower heads all the way up, and so on. Not to mention the low ceiling & pipes in the basement, where I know sororities have things like their hang-out rooms (idk the technical name lol). I think this really adds to the article and my personal sense of the injustice of sororities not having their own housing off-campus. Thank you for your comment!

Colleen B • Sep 15, 2023 at 12:48 am

Thank you Current (Tall) Whittie for the pleasant comment and adding your own perspectives on being tall.

I didn’t mention in my original comment but when I lived in Lyman my first year not only did my feet hang off the end, but Lyman actually has bathtub showers on the first floor so I would actually go a floor down to use one of those as I could back up enough to get my head under without potentially touching an opposite wall (actually all three of the places I lived at Whitman had bathtub showers so scoreeeeeeeee.

I can’t remember if the rooms had a specific name as there were the chapter rooms and then the lounge type rooms which I think hang out rooms work perfectly for. I appreciate you taking the time to comment and adding your own perspectives. I plan to be on campus next week for reunion so if you happen to see me feel free to come up and say hello!

Lastly know that tall women should definitely wear high heels because we don’t need them for height, we use them as a power move so all the high heels. My friends as a birthday gift got me a pair of 6inch heels (which tie up to the knee) which are just the most incredible (and painful after 10 min lol) shoes I own