How to grow a campus

October 28, 2021

Famous landscape architect John C. Olmsted declared that having a large, unbroken field in the center of Whitman’s campus would be a “practical impossibility,” although it would “undoubtedly be most pleasing to the eye.”

Alas, “it will be essential for convenience to have at least paths crossing it in various directions,” he wrote in a report for then–college president Stephen Penrose, who commissioned Olmsted to recommend a campus design in the early 1900s. Olmsted proposed an Ankeny “quad” with a large fountain at its center, from which paths would stem.

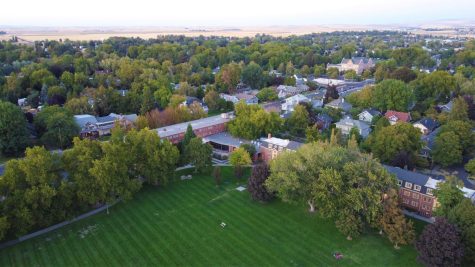

Yet here we are. Ankeny remains as unbroken as ever, save for snowy winters when students’ repeated treks carve muddy a desire-path from Jewett to the library. Olmsted would be pleased to know the field is beautiful, albeit arguably inconvenient.

Associate Professor of Art History and Visual Culture Studies Dennis Crockett’s recently-published pamphlet “The Greater Whitman, 1905-1912” chronicles Whitman’s early devotees’ pining for the college’s transformation from a “village school” into a prestigious institution. Ankeny was a key feature of the “greater” Whitman: Penrose and others were excited by the prospect of a “large quad [that] conveyed an appearance of permanence and prestige.”

In fact, they were greatly occupied with ideas of permanence and prestige—the kind epitomized by the elite East Coast schools they aimed to mimic. Archer W. Hendrick boasted to potential donors that Whitman has “grown from a village school of 1866 to a college of the New England type…What Harvard and Yale are to New England, Whitman hopes to be to the Northwest.”

To invoke the impressiveness of colleges in the class of Harvard and Yale, our campus should mirror theirs, Whitman’s leaders figured, and it had quite a bit of catching up to do. Crockett explained that in 1894, Whitman was “three wooden buildings”: College Hall, Ladies’ Hall and Gentleman’s Hall—an “unimpressive two-story box.”

Once the campus incorporated several brick buildings, including Memorial Hall, it felt more like a bona fide college campus: “the college had moved toward the cloisterization (albeit trapezoidal) that most of the professors would have recognized as a college campus,” Crockett wrote.

Cloisterization makes a campus distinct—and detached. The more clustered together a college is, the more separate it is from the surrounding community; as if the “cloister-like manner” of certain colleges was to “shield the scholars from the adjacent cities,” Crockett wrote. Some colleges, including Harvard and Yale, “were originally built to face their towns; they physically embraced their communities.” But in the nineteenth century, even these colleges developed into cloisters. Today, we’re concerned about the “Whitman bubble.” Perhaps this phenomenon has to do with our campus facing inward, surrounding a center bordered by Whitman buildings.

The “Whitman bubble” might have formed back then, during the college’s eager leap away from being a “village school.” It yearned to become a school unabashedly different from the one it would be without New England influence. Robert Allen Skotheim, in G. Thomas Edwards’ “The triumph of tradition: the emergence of Whitman College 1859-1924,” wrote that Whitman is a “transplant.” The school succeeded in its goal of joining a long-standing tradition: it is “the most traditional transplant in the Pacific Northwest of the elite New England college,” Skotheim wrote. So those leading Whitman into the twentieth century got their wish.

Plenty has changed in the one-hundred-plus years since they envisioned campus: Jewett filled in the northeast corner of Ankeny in the ‘60s; Whitman acquired an old hospital and tacked it onto campus; the recent addition of Stanton and Cleveland moved the center of campus south. Memorial is the only original brick building still standing.

Still, campus remains relatively stagnant. With big, sweeping changes few and far between, the focus shifts to day-to-day upkeep. Buildings remain still—but the natural parts of campus grow, change and require constant care. Enter the Whitman College grounds crew.

The eight full-time members of the grounds crew, and several student workers, do “whatever is needed as a team to make the campus,” arborist Kirk Huffey said. On a day-to-day level, they are indeed the ones who make the campus, especially its more beautiful features: the trees, shrubs and lawns.

Each crew member is assigned a “zone” of campus to care for. If you have intimate knowledge of how to care for grounds, you might be able to pick up on the different approaches zone-to-zone. Grounds crew member Cody Watson avoids spraying chemicals whenever he can, opting instead for laying mulch that prevents weeds from popping up.

“My main thing is, I always think about bugs and little critters and stuff like that, as opposed to [someone who] may not think about that when they’re doing something,” Watson said.

It’s a technique he’s spent some time honing for the sake of the critters. But he must also consider the appearance of what he’s working on.

It’s about “finding a happy medium where it doesn’t look trashy, and it’s kind of hidden, and leaving a thin layer as opposed to leaving it piled up,” Watson said. “At first I was leaving huge piles and it was just a bit too much.”

But Huffey hedges that, insisting “you’ve gotta use chemicals on some level.”

“You can never get away with never using it,” Watson said, while you’re “trying to keep up on suckers so that they don’t get hit with the spray.”

Huffey’s been here nine years, and in that time, he says the use of chemicals has decreased significantly. He pictures himself here for twenty years total. He’s excited for what’s yet to come.

“And so I’m gonna have all those years of watching my work, watching what happens, and continuing to learn as far as tree biology, [about] caring for trees,” Huffey said.

Another change to the care of campus plants? The amount of wood chipping around trees, Huffey says. (The wood chips are made from branches that have been taken down.) The use of wood chips is a big push in the arbor world, “so the trees are not competing with grass. So there’s been some creativity in that,” he said.

There’s more room for creativity and individuality in groundskeeping than you might expect.

“Somebody may prune a shrub a different way—there’s different styles of pruning. Even in the trees, there’s different styles of how you prune or what you do,” Huffey said.

While they each have specialties, much of the work overlaps.

“From pond cleaning to laying out logs and laying mulch, it’s a variety,” irrigation specialist John Sergeant said when asked what he does day-to-day. “The campus is so vast for a short crew that we really spread out and do a lot.”

“I’ve never been somewhere that you could be on a mower one day, digging a trench the next, or chipping brush or in a garbage truck,” Sergeant said. “Then to feed off each other in a knowledge sense, too, from bugs to arbors to irrigation … that’s the best part of the job.”

He encountered, one winter day, ladybug larvae, and thought of his fellow grounds crew member with an affinity for bugs.

“I sent a picture to Cody, he’s like ‘oh yeah, that’s a ladybug.’ So you get to learn the stuff as you go. Before I wouldn’t know who to text a picture to. So that’s pretty cool,” Sergeant said.

Sergeant noted that the pandemic was disappointing because the crew dynamic is great when they get to all spend time together on campus. So he’s grateful to have returned.

And they certainly spend a lot of time on campus. In the winter, they are sometimes notified the night before that they will be starting work at five the next morning—for the sidewalks must be cleared of snow.

Fortunately, they don’t have to worry about an elaborate series of paths on Ankeny.

If Olmsted and Penrose worked in terms of the grand, the grounds crew considers the seemingly minute: the critters, the mulch, the ways campus gradually changes over time.