Whitman’s archives piece together the past

November 15, 2019

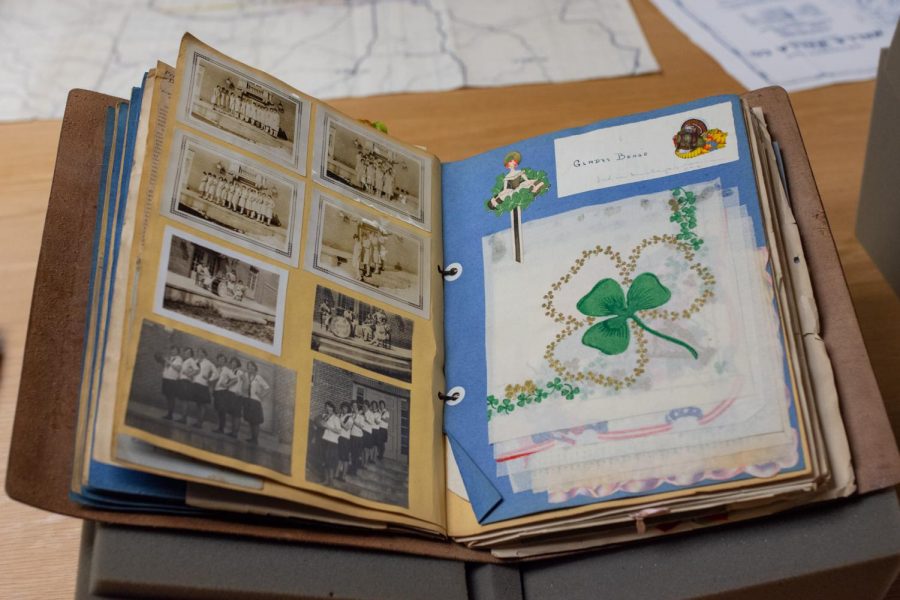

Tucked away behind moving shelves lies history, carefully stored and cared for by dedicated individuals.

Located in the Penrose Library basement, the Whitman College and Northwest Archives collection is a unique and underused space on campus. Aside from an initial visit during orientation, many students are unfamiliar with the offerings of the archives and its role on campus.

According to Ben Murphy, archivist and head of digital services, the archives house about 4,800 linear feet of material.

Additionally, Murphy noted, the archives are responsible for a rare book collection with about 5,000 volumes.

“Some strengths of the collection include Northwest history and culture, a collection of finely illustrated texts from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century and we have a significant, and growing with some recent donations, collection of artists books,” Murphy said.

According to Murphy, this semester 28 classes have made use of the diverse array of archival material, reaching 245 students. Outside of classes, there have been 323 visitors since July 2019. About 68 percent of the visitors have been Whitman affiliates; the remaining visitors are local community members or people traveling from outside the area to use the collections. Last fiscal year, there were 721 total visitors from July 2018 to June 2019.

Standing between researchers and the archives is not access, but knowledge of materials. To address this barrier, the archives have recently been increasing the availability of finding aids — documents that provide information on materials within collections and play a critical role in connecting the public with archival material. Dana Bronson, assistant archivist, has spearheaded this project with passion and expertise.

“When I started two years ago, I did a big survey of our vault and our holdings; about 80 percent of the holdings in the archives at that time had never been processed at all and about 50 percent of the holdings had no public access point at all so no one could ever know that we had them unless we told them we had them,” Bronson said.

As of now, Bronson and team have created about 400 finding aids.

“In terms of the NW manuscript collections those are almost 100% described now which is great,” Bronson said. “Now I’m pivoting more towards the college records about 50 percent of those are still undescribed so that’s definitely a big area of work.”

This kind of processing and researching is at the core of archival work. Bronson was drawn to the discipline herself in college after using the archives for class and then as a student worker.

Whitman archivist Dana Bronson.

“I think seeing history come to life using those primary sources is really exciting to me,” Bronson said. “In thinking about what I wanted to do for my career, I was a history major at the time, I was excited about the prospect of being involved with the archives because I had seen how through my research they had been used as sources of accountability and not only in the government section but a lot of human rights work has been done with archives to hold different regimes accountable.”

Sophomore history and English major Katy Sassara also found academic, professional and personal passion through engaging with the archives since her first year. As a student employee, Sassara does research and processing with new collections. She is also currently taking Library 150, taught by Bronson, where she learns about archival theory and history.

Similarly to Bronson, the archives have shaped Sassara’s future, illuminating her passions and future paths. Researching and working with collections has offered insight into her academic interests and their relationship to her professional goals.

“I have realized what I want to do professionally because of my job in the archives,” Sassara said. “I think it has led me to my majors pretty heavily as well because I’m intentionally majoring in the things that kind of meet at the archives.”

Her passion and enthusiasm was palpable. Such excitement infuses the work of these dedicated archivists and brings documents to life.

“It’s just so much fun,” Sassara said. “I have always loved doing research and listening to people’s stories and finding about people and the things that they do and the things that make them tick. It’s just a repository of all of that information from the past, for our archives, about 170 years. Because it’s a local archive it’s all that information in regards to a place that is very tactile and very real for me.”

Recently, Sassara recalls working with a new collection and realizing the owner lived in the 1920s down the street from Sassara, so she went and visited the house. This specific and geographical connection to history and research is powerful and inspiring.

“This woman that I am finding out about lived there and that was her life and she and her sister were there 50 years and you get to make the community more real and more multi-dimensional,” Sassara said. “It has really enriched my relationship with Walla Walla and I am really grateful for that opportunity.”

While archives can enrich community relationships, they can also challenge them. The issue of representation — of whose stories are told and remembered and what materials belong to whom — is one the archivists are currently grappling with.

“I don’t think people really think about the archives as a political space, but they really are,” Sassara said. “Both in the way that we deal with what we already have and the way we collect new stories and how we manage our relationship with the community.”

Bronson also discussed the political challenges facing the archives and the efforts to include formerly underrepresented populations. This endeavor is at the forefront of campus discourse and presents itself uniquely in the archives.

“From my perspective, something I have been trying to do and hope to continue doing is to get more representation from student clubs and groups on campus in the archives,” Bronson said. “We often have alumni or students doing research who want to know more about the history of things like the Black Student Union or different affinity groups on campus in the past and we just don’t have that many records from those groups because they weren’t actively collected at the time. So, we want to rectify that absence by being more active collectors today.”

Another avenue for addressing representation concerns is a new class taught by Murphy this coming spring. Library 160: Document/Represent Archives engages students in these issues to explore and discuss methods for creating collections that “document the history and politics of underrepresented voices both at Whitman and in the Walla Walla Valley,” according to the catalog description.

“Library 160 is specifically asking students to think about the history of different student clubs and organizations and different kinds of student populations and think about what groups or identities are not very well documented or represented in our collections and think about strategies for addressing some of those gaps and silences,” Murphy said.

This academic study of the archives fits well with another purpose of the archives: as an extension of the classroom. Working with faculty and students to incorporate archival material is a main element of Murphy’s role on campus.

“The thing that I enjoy most, and the main part of my responsibility is integrating our collections into the curriculum and working with faculty and students using the materials,” Murphy said.

While the archives may be daunting for students starting research, or seem unrelated to subjects beyond history or the humanities, everyone can take advantage of the opportunities for learning within the collections.

“Sometimes it requires creative thinking to think, how might I use archives in a project for me,” Murphy said. “We have materials that relate to environmental studies like sociology, politics, gender studies, race and ethnic studies, you don’t have to be focusing on the history of Whitman College or the history of the Northwest to find materials that might connect to some kind of larger discourse or theoretical conversation you’re having in class.”

The physical and tactile experience from archival documents and primary sources emphasizes and expands students connections with their studies. In the experience of Eric and Ina Johnston Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion Katharine Mershon, incorporating the archives into academic curriculum is a unique and powerful tool for student learning.

“With the expertise and skills of Whitman’s archivists, my ‘Ethics of Apologies’ course has visited the Northwest archives the past two years. While we spend plenty of class time reading and engaging with the histories of settler colonialism and Christian missionaries in the region, there is something particularly powerful about students having the opportunity to encounter primary sources as tangible objects that they can see and hold,” Mershon said. “What was initially an abstract concept becomes a material reality, giving students a powerful and historically-informed understanding of the college and the region. I’ve found this experience to be among the most memorable and valuable for student learning.”

Experiences like these are meaningful, cementing the value and role of campus archives. Bronson and Murphy both mentioned the desire to increase student use and connection with the archives to expand the reach and benefit of archival experiences.

“We have seen more and more students coming in over the last couple years and I hope that we continue to grow as a place where students want to come to learn more about the history of the college and the region, either for a class, personal interest, creative project or thesis because it really comes alive when students are down here encountering that for the first time,” Bronson said.

This idea was echoed by Murphy, who acknowledges the potentially intimidating atmosphere of the archives and encourages students to go beyond that anxiety.

“Archives exist to be used. We want students in particular to use our collections, to study them, handle them, learn from them,” Murphy said. “I know archives in general can sometimes be a little intimidating we do our best to try and be welcoming, we just always want to communicate that these materials exist for students and again we have access to more unique and rarer materials than some colleges of our size have.”

The accessibility and welcoming nature of the archives beyond their potentially intimidating front was also emphasized by Sassara. She mentioned frequently flagging interesting documents during her shifts and returning later to learn more.

“You literally can have a question or an interest or a person or anything, like go in thinking I don’t know anything about what the psychology department looked like in the 1970s and I’m sure there is information there and you can go and look at it and touch documents and there’s photos and all sort of information,” Sassara said.

According to those most familiar with the archives, they are a place to inspire, engage and encourage curiosity, meanwhile adding depth and dimension to academic study. They are a space constantly changing, growing and adapting, where interdisciplinary studies meet political conversations, personal interests and more. They are curated and carefully cared for, designed for learning, enriched with the richness of human stories and available to everyone.

“We are here for you. We are here to be used,” Bronson said. “This history is your history and it is here to be shared and we want people to contribute to that history as well.”