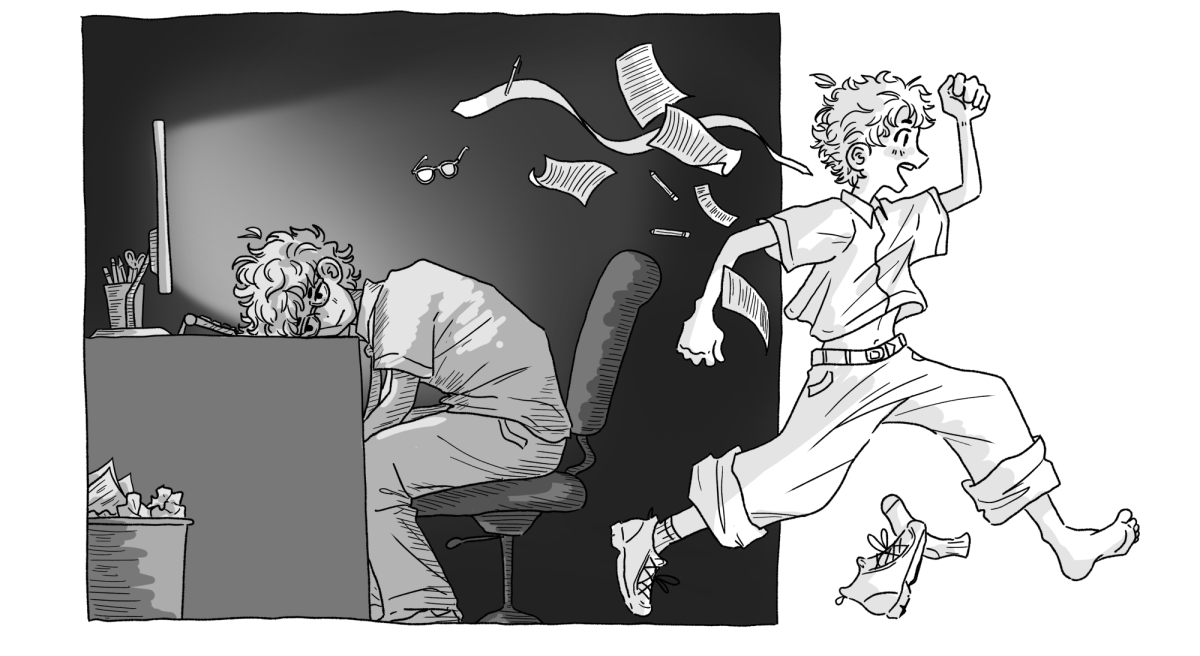

Some students stick with coffee to muscle through college workloads, some use prescription neuroenhancers. According to many students at Whitman, the two aren’t necessarily all that different. In an era of overzealous ADHD (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder) diagnosis, study drugs: primarily Adderall, Ritalin and Concerta: have carved themselves a niche in competitive college and high school campuses without attracting a particularly negative or criminal connotation.

“So many kids shouldn’t be on Adderall daily, but once in a while isn’t so bad,” said an anonymous Whitman student in a survey circulating this week on the use of study drugs on Whitman’s campus.

Of the 193 student respondents, 13.5 percent have used study drugs and the vast majority: 87.2 percent: of these students did not have a prescription. Of this group, 34.5 percent claimed one-time use, while 11.5 percent use study drugs once a month and 7.7 percent use on a weekly basis. A third of respondents specified particular usage habits, predominantly concentrated around finals and major project deadlines.

While we’re nowhere near endemic use, study drugs on the Whitman campus are fairly visible: at least to students. In nosing around for this article, I received a surprising number of offers, friend-of-a-friend sort of hook-ups, and general commentary.

“Everybody’s looking for Adderall these days . . . It’s that time of the season,” said a sophomore on Saturday. Several students expressed passing interest in the idea, piqued by the thought of increased productivity and the fabled focus promised by these study aids.

Conversely, the negative repercussions of using neuroenhancers are rarely discussed. Of course there are side effects: some users say they get real sweaty, and there’s always the danger that the resultant focus, motivation and inability to sleep might be misdirected on extraneous tasks: and it’s obviously illegal, but major problems on campus have yet to surface.

“It’s not an issue we deal with with any frequency,” said Claudia Ness, director of the Welty Health Center. That said, neuroenhancers have high abuse potential and Adderall is classed as a Schedule II drug by the Controlled Substance Act. Additionally, study drugs often work as appetite suppressants and can lead to potentially severe dehydration.

Senior Nikki Schulz conducted a study for her sociology thesis this year, investigating the role study drugs have for students coping with academic and social pressure. Of the 14 students involved, whose habits ranged from concentrated usage three to four times a week to singular experimentation, Schulz says most did not consider their use unlawful or immoral.

“A lot of my participants didn’t see it as a crime or a big problem on campus. They downplayed how deviant it is,” said Schulz.

Essentially perceived as performance enhancers for cognition, how is the use of neuroenhancers different from doping in sports? Might we reach a point where competition leads academia down the same road many feel professional cycling has taken? Is there anything morally wrong with doping if it creates a more capable, productive student body?

Unfortunately, study drugs don’t necessarily improve the quality of student work: they’re more an antidote to procrastination. Schulz found that most of her participants didn’t consider their usage unfair or iniquitous because they didn’t see the quality of their work improve. According to many participants, study drugs seemed to enforce existing bad study habits.

“Once you’ve used them, it’s easier to leave things to the night before,” she said. “[The common perception is that] it’s just something that people do to get their work done and not that big of a deal.”