Urban farmers attempt to transform suburbia into more than a sea of manicured lawns. As self-proclaimed “aspiring urban farmer” junior James Most said, urban farming is “producing food in a landscape that is not stereotypically a food-producing landscape … like chickens on a lawn.”

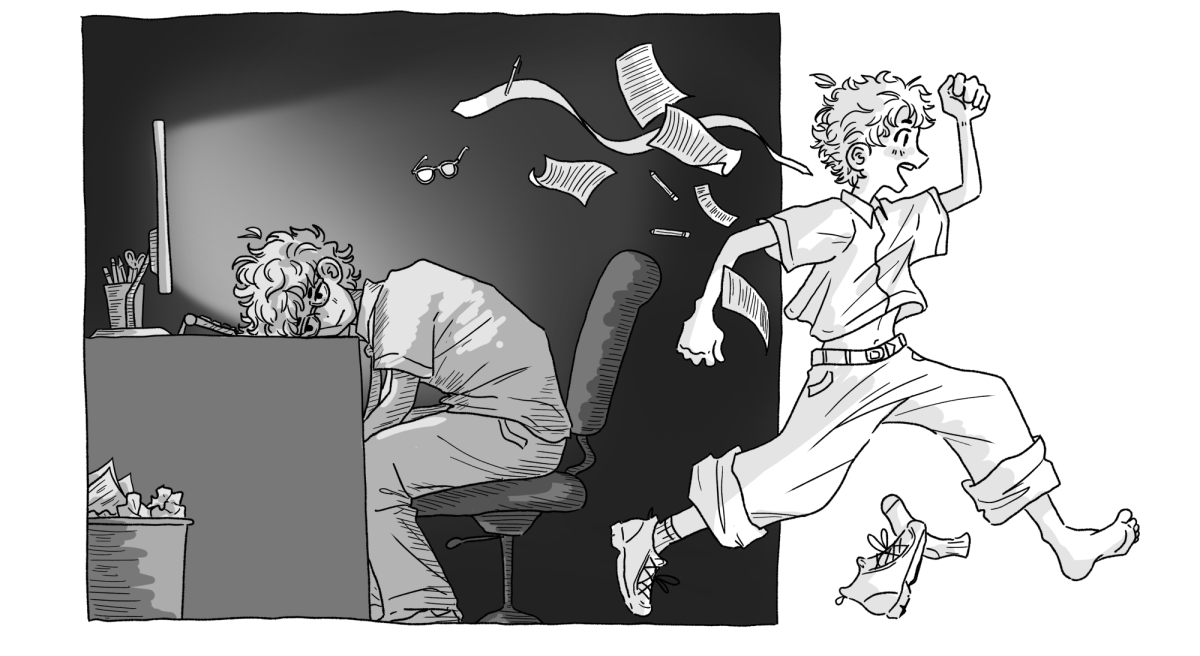

Most and junior Will Davidson have been “co-conspirators,” as they put it, in a series of urban farming projects this semester, from raising five chickens from birth to barbecue to beginning a gardening project in January. Their aim: to experience where food comes from.

Urban farming is not a novel concept. The roots of urban farming extend back to the Victory gardens of WWII, when suburban families planted gardens to produce fruit and vegetables as a patriotic war effort. There was also a “back to the land” movement in the 1960s and 1970s, prompted by disillusionment with the Vietnam War, Watergate and, more generally, consumerism and the growing divide between city and country. Helen and Scott Nearing, for example, left New York for rural Vermont to live self-sufficiently, publishing a book, Living the Good Life, about their experience.

Most and Davidson do not aspire, however, towards self-sufficiency. Instead, their goal is to experience where their food comes from. The specific challenge that they and their club, Food Not Lawns, have tackled is the student schedule. They wanted to design an urban farming project that could be successful on a semester system: taking into account that many students are mobile during the summer, leaving campus to pursue jobs, internships and travel.

Most and Davidson do not aspire, however, towards self-sufficiency. Instead, their goal is to experience where their food comes from. The specific challenge that they and their club, Food Not Lawns, have tackled is the student schedule. They wanted to design an urban farming project that could be successful on a semester system: taking into account that many students are mobile during the summer, leaving campus to pursue jobs, internships and travel.

Most acknowledged that, to many, their gardening project, which takes up a parking space behind their duplex, may not seem like a huge accomplishment. However, Most and Davidson started the plants in January, which is why the two tomato plants, for example, are beginning to produce now. At the supermarket, hothouse tomatoes are still prevalent; vine-ripened tomatoes won’t show up until summer.

Most cited the chicken project as their most successful experiment, not only because he and Davidson experienced the entire process of raising meat but also because of the wider interest it generated in the community.

“[It was the most successful project] because of the buzz it generated … [the feeling] that other people want to try this … [as if] someone hit the boulder with a golf club,” said Most.

Next semester Food Not Lawns intends to build and give away lettuce beds, as the beds were one of their most successful gardening projects. They hope to share the experience of producing food. Food production, after all, is about more than just the harvest.

“[There are] therapeutic benefits of being around growing things,” said Most. To join the club or for more information, e-mail mostjr@whitman.edu.

The Organic Garden is another way to get involved with food production on campus. Open gardening is held on Fridays from 3:30 to 6 p.m.

Food Not Lawns and the Organic Garden are ways to get involved in food production now and to gain valuable gardening knowledge to store up for that “rockin’ garden” you plan to have later. Furthermore, getting involved means eating the “local-est local” food.

“[The American food system] sends shock waves out everywhere, we export so much of our subsidized grains and import so much,” said Most. Eating locally is one way to decrease impact on a global scale.

There are many opportunities in Walla Walla to eat local, organic produce and meat. Thundering Hooves, in the Walla Walla valley, raises grass-fed cattle from birth to slaughter. They sell a variety of products in town at Thundering Hooves Meat Shop, located at 2021 Isaacs. Check out their Web site at thunderinghooves.net.

The Farmer’s Market, which opens again on May 5, sells a variety of local produce (seegofarmersmarketwallawalla.com for more information). Andy’s Market, in College Place, also sells local produce. In addition, there are two Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs in Walla Walla: “Ideal Organics” and the up-and-coming “Welcome Table Farm.”