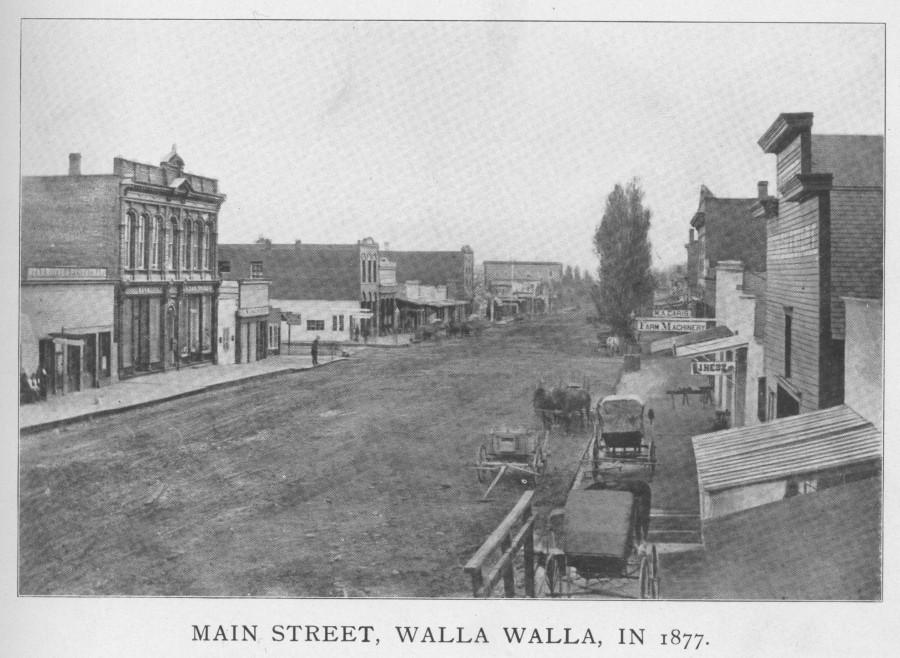

When Walla Walla was founded, it was, in the eyes of many, likely to be nothing more than a modest agricultural center. The gold rush shamed that prediction for a while. But the quality of the Palouse hills for agriculture ensured the area’s longevity, as it does today. Palouse is an altered spelling of the French noun, “pelouse,” meaning “area of land with short and thick grass.” The Palouse had been excellent grazing ground, but it wasn’t until 1864 that it was found to be ideal for farming. The discovery set off a migration into the hills, and farmers north and east of Walla Walla were soon producing more food than they could sell.

Waitsburg, just northeast of Walla Walla, profited from the new industry. But Dayton in particular, further along today’s Highway 12, grew up in a hurry. In 1872, the region’s population had grown enough to start a small town at a bend in the Touchet River. A surprising amount of money was invested into Dayton in a short time. A flour mill was quickly followed a post office. The post office led to an inn, then a fulling mill, then a church, then a school and, somewhere in the midst of it, our very own A. J. Cain.

It is hard to know exactly why Cain left Walla Walla. There is every indication that he had a mildly successful, pleasant life. Perhaps he wanted to shake things up. Others from Walla Walla had relocated to Dayton for new opportunities. Whatever the reason, Cain moved to Dayton and founded its first newspaper, the News, in September of 1874. With it, Dayton’s name was “heralded abroad,” as historian Gilbert says, and it brought in residents from other regions. But the paper was also, like Cain, decidedly democratic. If Cain had abandoned Walla Walla, he had not abandoned politics: by 1875, he helped to give Dayton the political clout necessary to push for its own county.

For the settlers of the Palouse, traveling to Walla Walla––the county seat––for legal business was a hassle. In 1869 the residents of Waitsburg had tried, unsuccessfully, to split the county in two. Dayton was founded in 1871 even farther away, creating further agitation. Soon, another attempt was made: on April 17, 1875, the Walla Walla Statesman printed that “General[1] A. J. Cain is down from Dayton, and reports everything lovely in that active town. Just now, the General is greatly exercised over the county question.” It seems that Cain was using his legal expertise to prepare Elisha Ping, prominent Dayton resident, to represent Dayton’s cause in the state legislature.

This rather innocent report in the Statesman seems to mask the issue, for the citizens of Walla Walla did not want to see the county divided. The new county would cut off Walla Walla from most of its agricultural and timber resources, annexing Waitsburg to boot. Walla Walla sent its own, opposing delegation to Olympia to no avail. After one hiccup, a modified bill (more modest than the first) created Columbia County in the fall of 1875.

Dayton was thrilled, but Walla Wallans were so riled up that they made overtures to Oregon State. Portland politicians were more than happy to provide for this annexation; they introduced two consecutive bills in the national legislature to cede to Oregon everything south of the Snake River (see visual), probably delaying statehood in Washington for several years. In addition to the “county question,” Walla Wallans cited financial reasons for their anger with Olympia, saying that they had been exploited for taxation by “the People of the Sound.” The residents of Dayton, on the other hand, were not eager to jump ship. As historian Gilbert writes, their “feathers had not been ruffled.” In the end, both bills failed despite realistic chances of success.

For his efforts, Cain was commemorated “the Father of Columbia County” and rode this success to office. After he established Columbia County, he was elected county auditor with 70% of the vote (a net 369 of 520). Perhaps we can better understand his obituary (printed in Part II) in this light. At this stage, he looks like someone who “could have occupied the highest position in the gift of the people.”

Surprisingly, Cain disappears from the record just a year later, in 1876. If he ran for office again, he lost. We might expect a man called the “Father of his County” just two years earlier to maintain political support. Perhaps Cain was in poor health. After all, he would die three years later in 1879. Or maybe there is something to the allegation that Cain had a “partiality for the drink,” after all. For whatever reason, Cain failed to capitalize on a success. Moreover, Cain’s success probably came at a cost; it would not be surprising if he had lost face in Walla Walla when he had quite obviously opposed his two-years-hence hometown. It is hard to explain why Cain felt so strongly about Dayton having its own county. Clearly, Cain had a political mindset. But there is much that remains unknown.

These mysteries are part of the reason that I find Cain so compelling. In many ways, he was typical of his time: a self-made man caught up in the wild growth and expectation of the period that marked the early settlement of this area by whites, when the names of towns, borders, and buildings––so permanent, to look at them now––were decided in the moment. But Cain was also exceptional: he was a lawyer, businessman, and prominent politician who left his own mark on the land. In a history book full of Bakers and Boyers, it can be easy to forget a man with a meerschaum pipe.

[1] In Part I, I mentioned the possibility that Cain had served in the military. Further sesearch indicates that he did. In fact, Cain was the very figure responsible for accosting the first miners to arrive at Orofino in Nez Perce territory. Cain was in charge of Indian Affairs for the region and tried, with animous opposition from the residents of Walla Walla, to stop the influx of miners to the rich gold fields. That story is quite dynamic and makes Cain a more important figure than I had originally estimated. Years later, in 1878, the people of Dayton found their situation tenuous when the Nez Perce, aggrieved due to the impact of exploitation of the gold mines, declared war. I like to think Cain appreciated the irony of the situation: the expeditionists who had failed to consider the consequences of their actions fifteen years earlier were witnessing them firsthand. He was probably not amused.