“Promised Land” Hits Close to Home: Indigenous Struggles in the Northwest

December 7, 2017

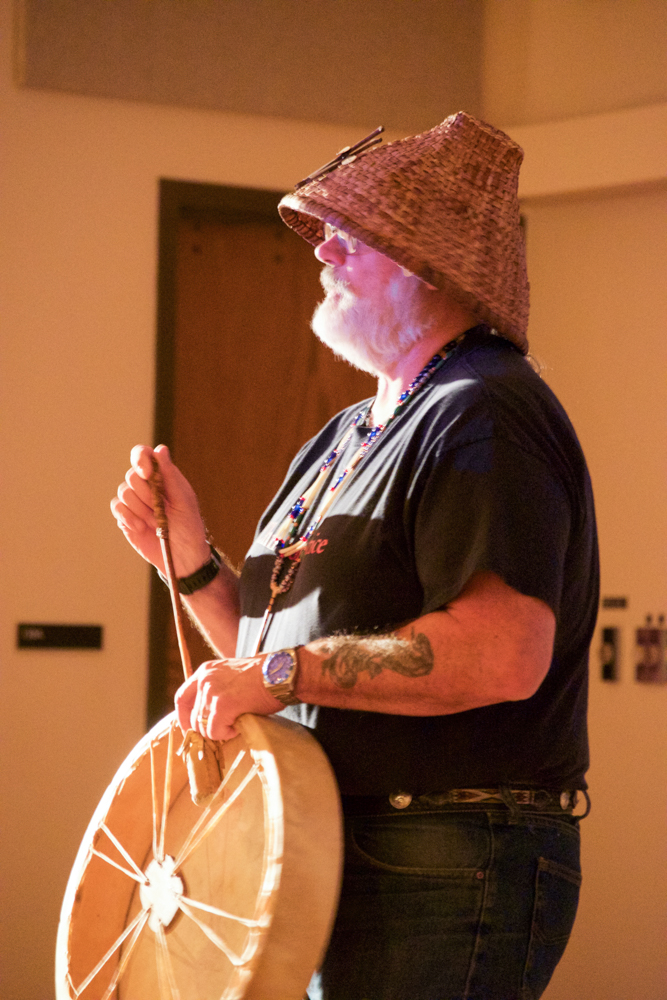

The film “Promised Land” addresses the ongoing political struggle of various indigenous tribes in the Pacific Northwest. On Tuesday, Nov. 29, the award-winning social justice documentary was shown in Olin Auditorium, followed by a panel consisting of filmmakers Sarah and Vasant Salcedo and Vice Chairman of the Chinook Indian Nation Sam Robinson.

The documentary explored the fight of the Chinook and Duwamish tribes for federal recognition, which has been denied them even to this day. Recognition from the government shows the sovereignty of the Native American governments and is important to them for that reason.

However, the documentary also emphasized that despite the U.S. government’s refusal to recognize these tribes, they still do exist—no government can take that away.

“It doesn’t really matter what the government says as far as identifying who these people are, other than the fact that resources are needed,” Vasant Salcedo said. “These people know who they are, and there’s a lot of pride and there’s a lot of joy and there’s a lot of humanity found in that. The resolve is great there, the resolution is great there. They know who they are, and they know where they come from, and there’s a lot of power in that.”

Unlike many documentaries, this film did not have an ongoing narration. Instead, it featured only the voices of the members of the Chinook and Duwamish tribes who were interviewed, leaving out any influence from the filmmakers.

“The wonderful thing about film is it’s a lot easier to take yourself out than when you’re writing about it,” Sarah Salcedo said. “What I really loved about film, and this is really to quote a Chinook Nation member Aaron Jones … he says that this is a ‘modern oral tradition’ that we’ve gifted the tribe. It didn’t start out that way, it just started out by us recognizing that we’re not part of these communities, so we needed to step back and just provide the amplification.”

By stepping back, the filmmakers provided a platform on which tribe members could make their voices heard and put their struggles to the forefront. This was much needed; their struggles have been long-running. Especially frustrating is the misconception that treaties give rights to indigenous people. According to the documentary, treaties reserve rights that already belong to native tribes such as the Duwamish and Chinook that were supposed to be promised. Given all of this frustration and disappointment, it seems amazing that tribe members are able to maintain hope in their fight.

Sarah Salcedo spoke to this aspect when she recounted what Chairman Tony Johnson of the Chinook Nation voiced.

“It’s the responsibility of him [Johnson] to carry on the fight of his ancestors, as it was their responsibility to carry on the fight of their ancestors, so if he becomes weary now, how is he going to pass on the stamina to fight into his children?” Sarah Salcedo said. “It’s not optimism, but it’s resilience, and the love for the people feeds that resilience.”

While many Whitman students may feel removed from all of this, the struggle outlined in the documentary is very relevant, especially given recent debates about the Whitman’s legacy. Assistant Director of the Intercultural Center Maggi Banderas, who initiated the Whitman film screening and bringing the Salcedos to campus, explained why she thought it was important to bring this event to Whitman, especially given that Whitman is built on Umatilla land.

“I think that the big message of the film is a reminder of whose land we’re on, and it’s often very easy to forget and how tribes like the Chinook and the Duwamish are struggling to even get that recognition from the government,” Banderas said.

Beyond recognizing whose land we are on and how important the struggles of indigenous peoples are, the question of what allies can do remains. The Salcedos maintained that action beyond just recognizing the issue is key.

“In our social media culture, we’re so used to liking things and then scrolling on,” Sarah Salcedo said. “We’re not used to participation.”

Sarah Salcedo maintained that community members need to go to the tribes and ask how they can help and engage.

“We hope that audiences feel a sense of obligation to go to these communities and learn and ask how they can help,” Sarah Salcedo said. “It’s not just about consciousness, it’s about action … For students here at Whitman, I’d encourage them to go to the Umatilla and say, ‘What do you need? Here are my skills. Can that be utilized by your community in any way as you guys fight for sovereignty?’”

In asking these questions and taking the initiative to recognize the wrongs that need to be righted, and going a step more to get involved, one may join the movement toward indigenous people recovering the land that they have been promised.