100 Concrete Books: CLOUD Examines Our Relationship to Knowledge

November 9, 2017

Associate Professor of Art, Michelle Acuff and I sit on a wooden bench outside the Allen Reading Room (known to regulars as the “Quiet Room” – Acuff calls it a “temple”). They hold in their hands two halves of a concrete book. It broke earlier that day. The book’s smooth stained exterior gives way to jagged, harsh rock.

The once mysterious, tempting, unopenable book is reduced to fragments. But when Acuff holds the pieces back together, the mystery returns: I can almost imagine something written inside.

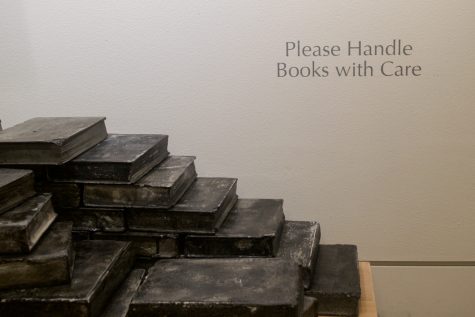

One hundred of Acuff’s concrete books (if they can truly be called “books”) have found a home in Penrose Library as part of a new sculpture called “CLOUD.” Most of the books are stacked on a platform near the entrance to the Quiet Room, a few beginning a process of circulation at the whim of anyone who decides to pick one up and move it elsewhere within the building.

Movement of the books can be tracked using Instagram: each book has a number on its cover and a corresponding hashtag. Snap a photo of a book in its new location, tag it appropriately, and it will appear in the catalog on the iPad near the sculpture’s home.

Acuff’s catalog is a kind of disruption of the Library of Congress system that Penrose uses to organize its materials – a strict categorization of knowledge by class and sub-class. There is no particular order to the way the books in “CLOUD” must be dispersed; it is up to visitors of the library to decide for themselves where the books belong.

In their artist statement, Acuff calls their books “archetypal … the age-old container of ideas cherished by the academy.”

But the way we interact with knowledge is changing. Acuff recalls, as a child, their encyclopedia set: finite, ordered, authoritative (though, by no means, “objective”). Now we have Wikipedia, with its seemingly endless hyperlinks, references and evolving list of authors.

“I’m way more suspicious,” Acuff tells me. “Way more certain that I will never know everything that needs to be known.”

This transformation in the way we access knowledge is, in part, why the sculpture is titled “CLOUD.”

“I have a pretty hearty relationship to language,” Acuff says when I ask them about the title. “The vernacular of the cloud – ‘oh it’s in the cloud’ or ‘the cloud is all around us.’” The cloud, they say, is “where information lives.”

Considering the structure of the sculpture, the word “cloud” takes on another meaning. As the books disappear throughout the library, they form together a kind of cloud of their own: shifting, expanding, contracting.

Acuff’s 100 concrete books were born of the same original: a $3 purchase they acquired from a Walla Walla thrift store around the time they first arrived at Whitman in 2007. When I ask if Acuff remembers the original book, they say they don’t – and it was destroyed in the process of creating the concrete molds.

If a cloud is light, amorphous and transparent, each of Acuff’s individual books is the opposite: weighty, solid and uncompromising. There’s a tension in the piece between old and new, between permanence and change.

These books have led long and complex lives, appearing in various exhibits before “CLOUD.”

The story of the books began around 12 years ago while Acuff was teaching at Millsaps College, a small liberal arts school in Jackson, Miss. Having never lived in the South before, Acuff says the poverty was “startling.” Millsaps is located in the city – a gated community. According to Acuff, “there were guard shacks, and you had to show an I.D. to get on campus.”

Stark racial and economic inequity, crime and a landscape Acuff calls “rubbled” — it was here that Acuff first conceived of the idea for the books.

“All this stuff came together in this object: cement books you can’t open,” Acuff explains. “Books that are just like the built environment. Just like the sidewalks, the streets. Discarded fragments, ruins, basically.”

I ask if the unopenable books are a commentary on accessibility in academia, if they parallel the gated community and guard shacks of the college. They haven’t thought about this before, but agree that it’s a possible interpretation.

We gaze out onto Ankeny Field, and then they turn to look back at Penrose.

“This is a unique building,” they say. “The architecture makes visible the activity inside it. It also articulates a friendliness to the things outside of it. It wants you to make connections across that barrier. This is a special space.”