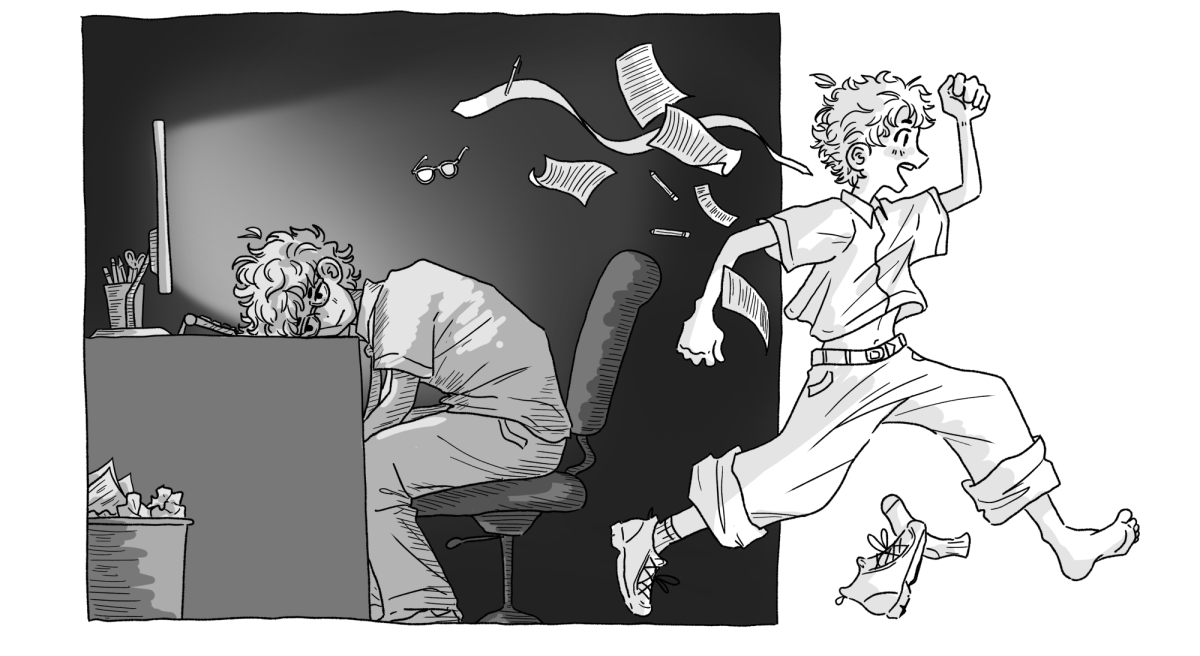

The feeling of motionlessness when the credits roll, like all the entropy has been sucked out of you by the sheer power of what you just watched – that’s the feeling we chase. You’re left bottled up; the rush of opinions, interpretations and emotions building, just waiting to spew at the first unsuspecting person who asks you “watch’a think?” – that’s the feeling we chase. Something that spurs you to move, that powers you despite your empty stomach – that’s the feeling we chase. I love movies, and I’m sure you do too, but more and more it feels like I’m chasing a memory instead of a possibility. I go back to my comforts instead of searching for the next character-defining two hours. Robotically clicking through the hundreds of slop shows looking for a gem I’m not even sure exists. Eventually, I found what I was looking for – smack dab in the middle of India.

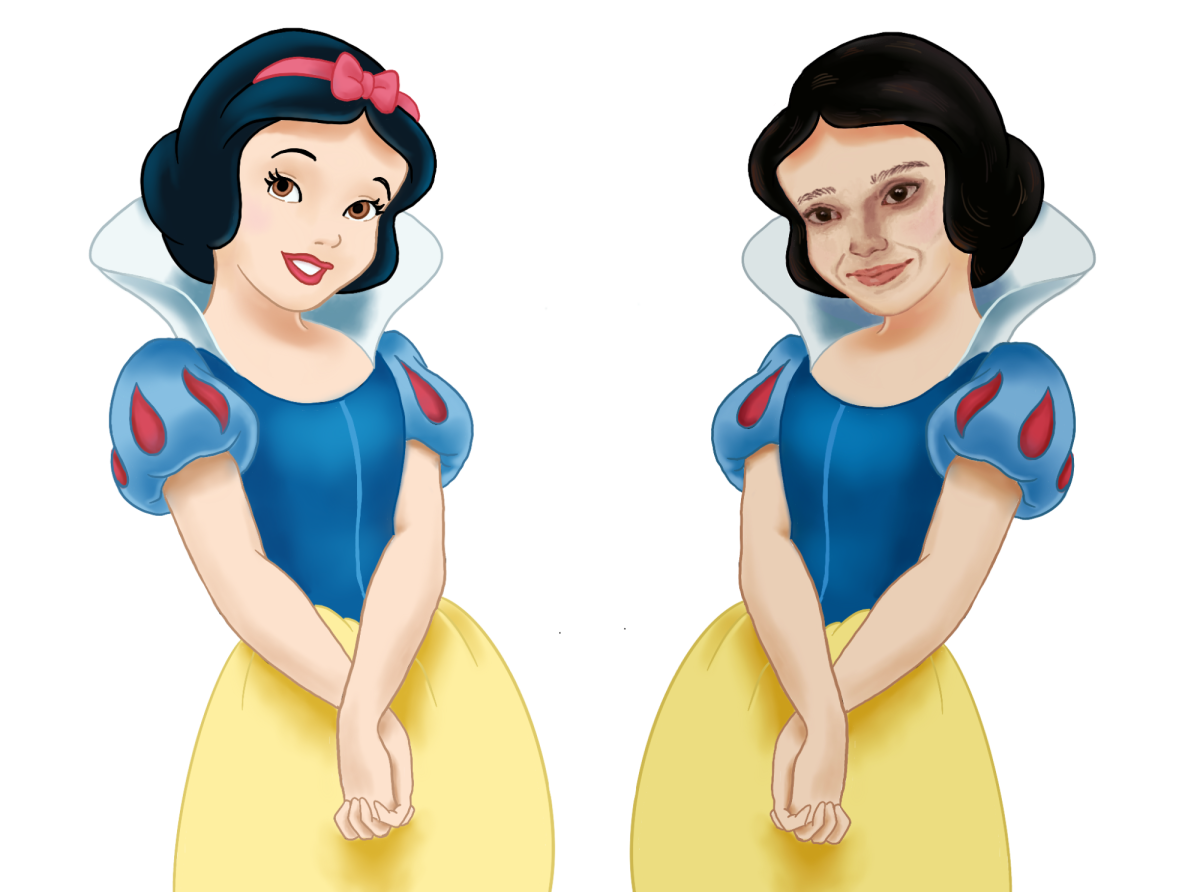

It’s no secret that the Oscars have seen a precipitous decline after their peak in the mid 2010s. Each year, declining viewership and a larger disconnect between audience and critic scores compound, making the once famed award show feel more like self indulgence by Hollywood big shots than an appreciation of art. From a “lack of representation” to “too much DEI,” if you are online, you are barraged with constant — often contradictory — claims as to why the once great award show is now a shadow of its former self. Unsurprisingly, the 2025 Oscars are shaping up to be no different, with controversy already ablaze weeks before the show even happens. One musical currently sits upon the inferno that is the Oscars… “Emilia Pérez.”

Jacques Audiard’s now award-winning musical has been the center of public discourse that has ionized audiences’ disdain for the Oscars. The musical and its cast have received a variety of critiques: from boycotts to the cast’s political views, the outrage has been constant. However, central in all of it has consistently been director Jacques Audiard.

A former English and French-language director, and someone who himself does not speak Spanish, audiences have been critical of Jacques’ choice to create a Spanish language film with a cast of mostly non-Spanish speakers. These criticisms seem to be born out in the final product, with many film critics speaking about the exploitation of Mexican culture within the film. To many, it appears that Audiard’s engagement with Mexican culture was only deep enough to adopt an aesthetic and not a genuine attempt to properly represent a place he was personally unfamiliar with.

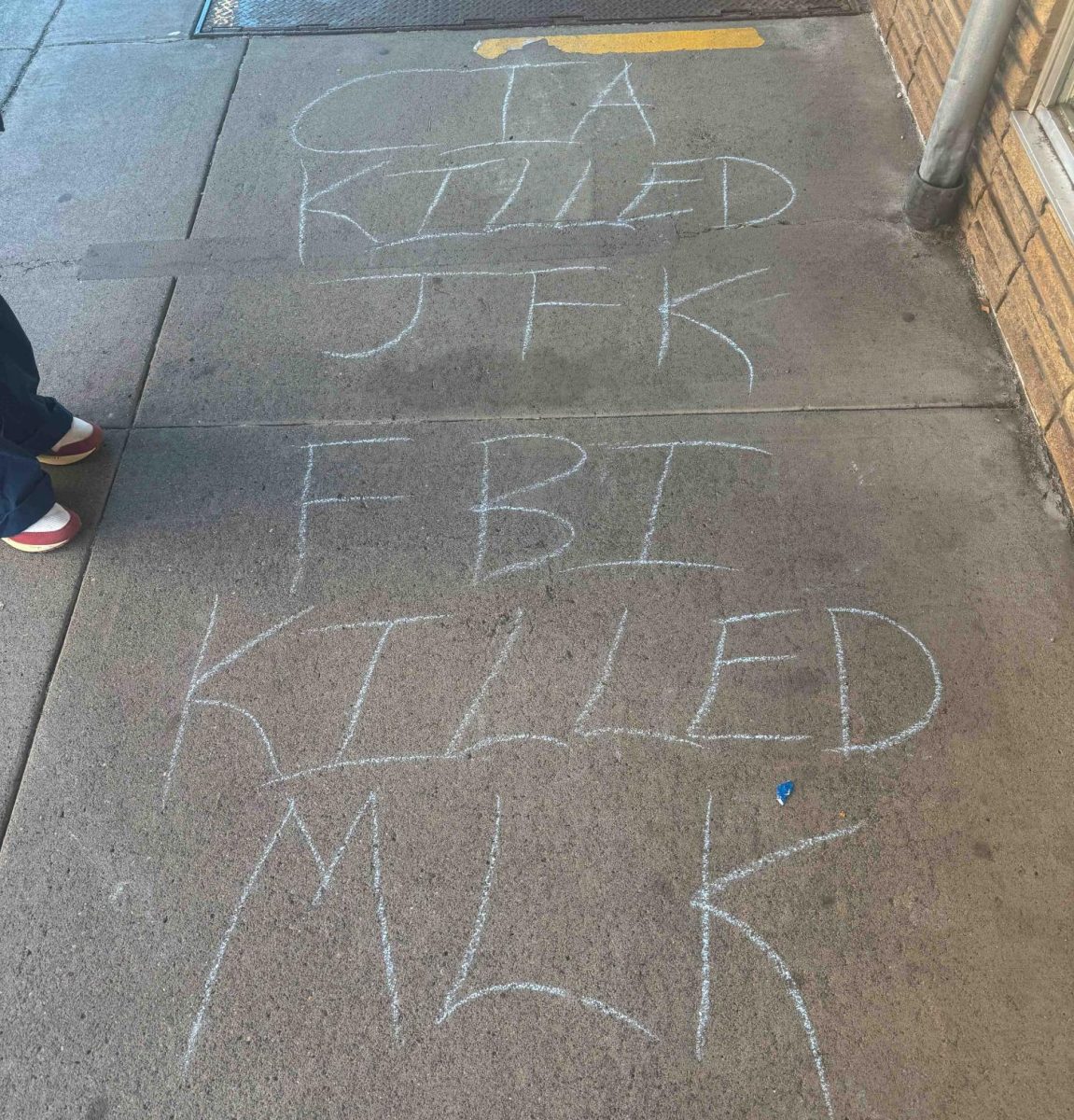

What interests me, however, is why Audiard chose to do this. He has already found critical acclaim for both his English and French-language films; no one has questioned his competence when dealing with languages he understands. Charitably, one reason could simply be creative vision; he was set on adapting “Écoute” (the source material for “Emilia Pérez”), with him saying in regards to Spanish, “It’s a language suited for singing.” However, he could be jumping on a new trend within the Oscars, which is the rise of foreign-language films within the Academy.

Bong Joon-Ho’s 2019 movie “Parasite” was a historic film in a myriad of ways, but most importantly it was the first foreign-language film to ever receive the pinnacle of all film awards – the Oscars “Best Picture.” Previously in the award show’s 90 years of life, only 11 foreign-language films had ever been nominated for a best picture, with only four of those films being in non-European languages. However, since Parasites’ historic win, eight foreign-language films have been nominated for best picture, an almost 15x increase.

Much like the Oscars, Hollywood as a whole has seen a decline post-COVID-19. Box office numbers have dropped year to year, with money-printing IPs like Marvel now draining money with each new release. Yet, audiences have not stopped watching shows and movies, with statistics showing that audiences in 2025 are consuming digital media more than ever before.

The decline of Hollywood has been accompanied by the rise of streaming platforms such as Netflix and Hulu, which currently dominate United States viewership and continue to rise year to year. Thus far, Hollywood has failed to effectively adapt to this new landscape as box-office numbers continue to fall. This decline has been coupled with a rise in foreign-language shows and movies, which are taking streaming platforms by storm.

Competition for viewership is no longer geographic – you are no longer limited by what theaters movies are in or what channels a show is broadcasted on. The contest for eyes has increasingly relied on the media itself. Shows like “Squid Game,” with a unique premise and striking visuals are now chosen over more formulaic English-language shows. Hollywood isn’t our only option – we can find the next big movie anywhere.

In 2020, if you asked the average American about Indian cinema they would probably bring up Bollywood – India’s Hindi-speaking film industry. Bollywood’s industry impact rivals Hollywood’s in magnitude, bringing in billions of dollars a year in revenue from both domestic and foreign audiences. Due to its size, Bollywood is also one of the only film industries that regularly has international film releases, which means international audiences are often exclusively exposed to Bollywood produced films from India. However, in 2022 a relatively unknown movie industry – in a language that few westerners know exists – let the world know that Bollywood wasn’t alone in India.

From the state of Telangana in central India, director S.S. Ramajouli’s historical epic “RRR” let the world know that Tollywood (Telugu speaking cinema) is a serious player in Indian film. “RRR” was one of the first Telugu films released on Netflix and was the number one most watched movie on the site for over two weeks. “RRR” also found critical success with its song “Naatu Naatu” winning the 2022 Oscar for “Best Original Song.” “RRR” paved the way for an entire industry to enter the zeitgeist of Western viewership, as following its meteoric success, over 100 more Tollywood movies were added to Netflix’s catalog. This year alone, Netflix has spent an estimated 1000cr (10 billion dollars) on buying the sole rights to stream certain Tollywood movies on its platform, largely thanks to the breakout success of Ramajouli and “RRR.”

One night my friends and I were looking for something to watch. We had become bored of “Criminal Minds” and “Doctor Who,” so we decided to look through the “New & Popular” section of Netflix. Most of it looked exhaustingly formulaic, or were movies one of us has already seen in theaters. However, eventually we came across an interesting looking movie titled “RRR,” and without much fanfare we decided to click play. For the over three-hour runtime I couldn’t take my eyes off the screen. “RRR” made creative choices an “Avengers” movie would never make; it did things I had never seen from any Hollywood movie. It just felt fresh.

“RRR” is a Romeo and Juliet story – or more aptly a Romeo and Mercutio story. It follows the converging stories of Alluri Sitarama Raju and Komaram Bheem as they fight against British colonialism. Bheem is a guardian of a small village who, after one of the village’s little girls is enslaved by the British governor, makes it his mission to save her. Raju is a British constable who, after the slaughter of his village at the hand of the British, has joined the enemy in an attempt to secure weapons for resistance fighters.

While the movie has the broader plot of kicking the British out of Delhi, the story centers on the friendship between Raju and Bheem – spending most of the runtime focusing on the brotherhood and conflict between the two.

In media criticism, “nuance” is so often used as a synonym for good: the more a movie has the better it is – which I believe is a misconception, one which “RRR” completely eschews. Nuance, if done incorrectly, can bog down a movie, making it feel like an essay.

Raju and Bheem are larger than life; they are maximally heroic, kind and most notably, they possess superhuman abilities. Ramajouili himself described them as “superheroes.” It’s common in superhero movies to have upwards of half the runtime dedicated to an origin story, giving a slow and meticulous explanation as to how the titular superhero is able to accomplish all they do. Yet “RRR” doesn’t choose to do this. When Bheem overpowers a tiger, no character ever points out how superhuman he is; the movie never plays it as a joke or provides an explanation. Raju can beat back hundreds of people and cause shockwaves by stomping, seemingly because he can. Frankly, it’s refreshing. “RRR” doesn’t treat the audience like children, like we need to have an explanation for everything. Ramajouli knows that we know that we are watching a movie. We know this is a movie about heroes and that they are going to be heroic. Because “RRR” does not accept that everything must be explained, the movie feels much faster and more fluid, because the movie isn’t about Bheem jumping 20 feet high, it’s about his friendship with Raju.

Along with two inspiring protagonists, “RRR” also contains delightfully hateable antagonists – the British. I’ve never hated a character more than when Governor Buxton’s wife cackles with glee upon seeing a freedom fighter getting whipped with a cat-o-nine tail. Throughout the movie, the British are portrayed as purely evil and wholly incompetent. Within the movie’s logic, the only reason they still have power is their access to firearms. This unabashed acknowledgement of good and evil feels so fresh in a media landscape that so often buries itself with anti-heroes and twist villains.

“RRR” is a movie that will make you cry, make you want to riot, and leave you with the urge to make a marble statue of Bheem and Raju. It feels like “The Iliad” if Achilles never died.

Tollywood, Ramajouli and “RRR” are the just the heralds for what I hope will become a new way we engage with media. If you’re not yet convinced, let me implore you to watch “RRR” and explore the rich landscape Tollywood has to offer. We all seem to share the sentiment that has permeated much of our collective consciousness – we are bored of Hollywood’s constant sequels, and celebrity-filled cash grabs won’t cut it anymore. So remember when the Oscars come around on March 2nd that you’re guaranteed to have a better night if you ignore the three hour award show and watch “RRR” instead. You won’t regret it.