In Aaron Bobrow-Strain’s politics course, Whitman in the Global Food System, students approach the political economy of food from local, national and global perspectives so as to make advancements that might benefit all people at those levels.

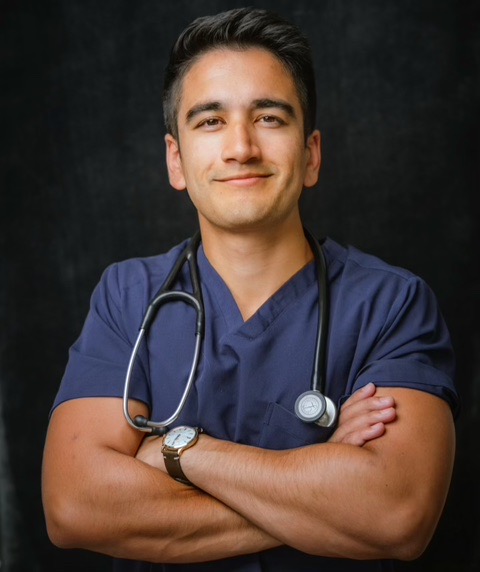

Professor Bobrow-Strain, who has studied at University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University and Macalester College, has been working on projects interested in political economy, cultural studies and critical human geography.

“The goal of the class is to give students a solid set of tools with which they can understand their world food system at a whole series of levels, from the politics of local food banking and emergency food relief in Walla Walla all the way to the kinds of global trade politics around NAFTA and the WTA,” said Bobrow-Strain.

Students learned about the development of the United States food system, particularly how it came to be what Bobrow-Strain called “this world grain goliath that dominates the world through the political use of food.”

The Global Food System politics class is studying food security in the Walla Walla Valley. Students will make recommendations to a local non-profit organization that is working on a proposal to the USDA to fund a major study of food security in Walla Walla. Research will look at the effectiveness and need of emergency food provision in non-profit organizations and government benefits.

Food security is the means by which people in a community will be able to access and afford safe and healthy food. Food security originated in the United States as an attempt to aid people through emergency food scarcities.

Food security and support quickly became institutionalized and was redesigned for longer term support rather than short term emergencies. Food Stamps and WIC (a special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children) are examples of national food security programs and food banks, soup kitchens and church groups that prepare meals for the homeless are examples of non-profit food security groups.

Bobrow-Strain talked about what it means to be an active citizen as opposed to an active consumer.

“There’s a lot of optimism about the sense that which Whitman students can change the world through their food purchases: by buying locally, by buying fair trade, by buying organic, whatever it is: that that’s a great way to change the world,” said Bobrow-Strain. “And in a sense it is. But I also see that as a kind of pessimistic perspective as well because often when I get with students talking about food politics, they don’t see any other way of changing the world other than through their purchases.”

Becoming an active citizen involves broadening one’s political imagination.

To students who tell Bobrow-Strain they buy organic because they don’t like pesticides, Bobrow-Strain suggests they organize to get the government to ban that pesticide. Food free of that pesticide would then be accessible to more people, not just those who could afford it.

“The goal is not to prescribe any politics, but to get [people] to think about using these tools of analysis from the class to understand issues related to food,” said Bobrow-Strain.

For more information about global food politics, Bobrow-Strain suggests “Sweet Charity: Food Emergency and the End of Entitlement” by Janet Poppendieck, “Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California” by Julie Guthman and “Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health” by Marion Nestle.