STEM pressure shouldn’t decide women’s futures

September 25, 2014

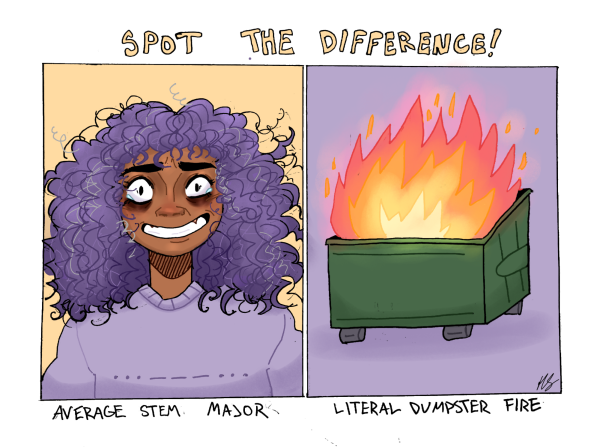

Illustration by Emma Rust.

First, I want to say that science fascinates me. It and the other fields in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) are crucial to society’s development and maintenance.

A recent report by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) found that nearly all STEM fields are dominated by men, and women hold just 20 percent of bachelor’s degrees in physics, engineering and computer science. In the past several years, the push to encourage more women to enter these fields has grown. Obviously I completely support this effort; we need women’s contributions. That being said, I have actually felt pressure as a female to go into these fields. In high school, as I excelled in pre-calculus, my teacher told me seriously that I should go into STEM because that sphere needed females.

In fact, I hated math. I knew there was no way I could make it my life, but I felt a sense of selfishness and guilt. I was a woman being encouraged to go into STEM and I was turning it down. Should I have done it for the greater good of my gender? Ultimately, I stuck with my passion for the humanities.

An article on Thought Catalog by a woman whose gender studies major is often degraded points out that the humanities are perceived as more feminine, something I hadn’t considered but makes sense. The sciences revolve around firm facts –– seemingly more masculine. The humanities deal with emotions and ambiguity, relating to the conception of women as more emotional, softer. The sciences also work with advanced mathematical concepts, still considered men’s area of expertise. That same AAUW report discusses boys’ historical outperformance of girls on math tests and research showing boys surpassing girls on quantitative and spatial tasks, although the resulting biases ignore other factors, such as the fact that spatial skills can be developed.

While these perceptions are likely to subconsciously discourage females from STEM, they might also make them feel, as I did, like they should enter STEM to defy gender expectations. A female humanities major may then be seen as less impressive. While I haven’t noticed a significant female majority in my own humanities classes, I have noticed differing reactions when students announce their majors. When I say “English,” the reaction is, “OK, cool.” When my female peers in STEM declare theirs, the reaction is usually, “Nice, that’s awesome!”

Again, encouragement and positivity for women going into STEM is crucial. I do not wish the response for them to be any less enthusiastic. I do hope, however, that women do what they truly love to do and not what they feel obligated to do for their gender. Perhaps this is a point for people recruiting women for STEM to add. If women love physics, they should study it. But if they love discussing philosophy, they should do that, because the humanities play a vital role in society.

One young woman’s article on The Huffington Post reminds us that the critical thinking skills and cultural edification provided by humanities studies are incredibly important for dealing with global issues. We need humanities students to interact with people and to help solve systemic societal problems, like poverty and discrimination, that don’t have one right answer. If we recognize that both areas are important in their own ways and we use the mutual skills taught by each to work together in combating global issues, we will undoubtedly be successful. Furthermore, if each of us engages in the areas we are passionate about, these areas will be stronger for it. Yes, STEM needs more women, but we get to choose the roles we play.

Andrea • Jun 3, 2016 at 10:31 am

I know it’s been a couple years since this article was written, but I have to comment because I’m a female college student right now trying desperately to decide on her major. I’m not too sure what the other two comments are going on about, but I have to tell you that this short-but-sweet article is 100% accurate.

I excelled in all subjects in high school, and even though I always had it in my mind that I would be some kind of English, literature, or similar humanities major (because of how much I love reading and writing), I found myself faced with parents, siblings, teachers, and friends who all threw lines at me like, “But where’s the money in that?” and, “You’re a smart girl – you should go into engineering/physics/computer science/the medical field! Not a lot of girls go into that!”

It only got worse when I started college. The friends I made were mainly engineering and pre-med majors who frowned upon all liberal arts fields. I did, however, have my interest piqued in the STEM fields because of how brilliant, hard-working, and high-achieving my STEM friends and family members appeared to me. Also, I honestly enjoy theoretical physics, computers, and building stuff, so I took some classes and liked them. But I’m still hemming and hawing on deciding on a major for a couple of reasons.

I still love the humanities with a passion! I have ever since I learned to read. But societal pressure on girls to go into STEM majors is, frankly, overwhelming. And though we are taught from kindergarten on up to rise above peer pressure, I can’t even put into words how crushing this pressure has felt on me for the last few years. I have come to feel that, if I major in the liberal arts and humanities, I will come massively short of meeting my true potential. But, I’m afraid that if I take on a STEM major, a huge and important part of myself will sort of fade into the background, and will I thrive and feel energized in a STEM career, anyway? How many years of school is it going to take before I discover my true passion, my real niche?

Maybe I’ve done a poor job of explaining myself here, but let me tell you – the struggle IS real. The pressure IS real. And for some women, it may be doing more harm than good, as well as wrongfully, pridefully shaming those who choose not to go into STEM.

And that’s what I think.

name • Oct 4, 2014 at 10:12 pm

We all have contributions to make outside or our field. For example, “Separate the weak from the chaff.” I doubt it was deliberate malaprop, but tasty nonetheless!

N. E. Bodé • Sep 29, 2014 at 10:06 am

As a woman in STEM, I was intrigued to hear your comments on my field of study. I’m glad to hear that you find science fascinating, it’s a nice parallel to how interesting I think words are. I won’t elaborate or specify whether it’s rhetoric, linguistics, sentence diagramming, romantic literature, or dirty talking that piques my interest. I’ll just leave it at a gross generalization that serves the soul purpose of a safety valve should I offend anyone. Let your imagination run wild with what words I find so fascinating.

Living in a post-feminist society, I find it fascinating how few op-ed pieces there are on how the humanities and social sciences are glutted with women, or how women make up an ever burgeoning majority of the work force. It’s often overlooked how females earn the majority of bachelor’s and master’s and almost half of doctoral degrees in biology, a major that falls under the auspices of the science in STEM. If you were to pick one student at random from Whitman campus, odds are it would be a female biology major. Case in point.

Somewhere between you “completely support[ing] this effort†to encourage women to enter the STEM fields and feeling this guilt-inducing “societal pressure,†you lost me. Your article hinges on a contradiction, the crux of which is continually shifting throughout. By the end, I can’t discern what you’re advocating with regards to women in the tech industry. You admit that “STEM needs more women,†but are against urging women to pursue the hard sciences as it impels them to do something other than “what they love.†If “women going into STEM is crucial,†we should do as much as possible to raise the 20% threshold, a number which is a litmus test of how well we’ve encouraged women to enter the sciences in the past. In order to raise that number, we can’t perpetuate this laissez faire culture, but instead should actively show girls all of the possibilities of a STEM career. Our current one-in-five standing is a result of inadequate encouragement for young women to pursue the hard sciences and mathematics. But you’re claiming that we’re pushing women into these careers too aggressively. Would you kindly enlighten me as to where this over-vigilant guidance manifests itself? Because as a woman in physics, I was never encouraged into this career path. I’m not saying I was actively discouraged from it, but no individual or societal entity urged me towards a physics degree. And based on the fact that I am usually the only female in the room at work (I work at a large enterprise in the semiconductor industry in the summer) or one of thee girls in certain science classes at Whitman, I doubt many of my peers are feeling this pressure either.

This begs the question: where is this endemic societal pressure for women to pursue the STEM fields that you refer to? I couldn’t find it on TV flipping through countless shows about lawyers and doctors. Wait, Silicon Valley is on HBO, I’ll watch for the inundation of female characters that society is pressuring me to become. A complete season later and there are still no female supporting characters, let alone leading ladies. There’s one semi-recurring lady who’s some CEO’s lackey, well that’s about as empowering as the secretaries on Mad Men. So clearly television isn’t where the burden lies. Is this societal pressure hiding on college campuses somewhere between the innumerable pre-law and pre-med students? Wait, is there a correlation between what the media portrays as successful positions and what teenagers choose as their potential careers, unknowingly entering super-saturated job markets that will burst like the hosing market? Huh.

It appears the only example of this alleged pressure you cited was a conversation with a high school teacher. One well-meaning suggesting does not constitute rampant social pressure. It was exactly that: a simple suggestion that I’m sure you teacher was aware would be heeded as well as any advice graced upon a teenager is, in one ear and out the other (did you take their advice?). I like how you noted that your teacher told this to you “seriously.†As opposed to ironically? And as for “excelling†at math, it was high school, we all excelled back then. But then this thing called calc III happens and “math†students hit this proverbial wall when math gets hard impossible; calc III is what separates the weak from the chaff. Take Real Analysis and get back to me on how stellar your scores are.

I’m still wracking my brain for the purpose of the declaration of majors comment. I thought you were all gung-ho to encourage women to do what they love, why shouldn’t lady techies get a response that emphatic? This article appears to be an enumeration of personal discontent with your choice of major and how society values certain fields of study more highly than yours. Society is hierarchical in nature and you chose your wrung on the ladder. You said it yourself that you “excelled†at math and therefore could have easily been hard science or mathematics major. You chose your path in life, don’t get jealous when people praise others for choosing a major that makes them inherently successful, well-employed directly after graduation, and overall BAMFs.

For whatever reason, people have latched onto the segment of the degrees awarded to women in STEM each year and have editorialized it to death. As much as I appreciate every humanities and social science major weighing in on how my gender and field of study are impacting society, perhaps we should both just stick to what we know best. I enjoy pearls of wisdom such as this article about as much as you enjoy being asked “What are you going to do with an English degree?â€