Muddy Frogwater No More

February 18, 2016

Ten miles away, just a hop, skip, and a jump from campus, a new species extinction crisis is emerging. Over the past ten years, Milton-Freewater, or better known by some as Muddy Frogwater, has been defined in part by its wooden frog sculptures.

The sculptures, however, worn beyond repair, will soon be gone.

“Everyone retires at some point, and it’s time for the frogs to retire,” said Community Development Supervisor Mike Watkins.

Milton-Freewater has adopted a number of publicity campaigns in its history. “Sweet Pea Capital,” the ”Apple Capital,” and “Home of the Low Cost Utility” were tried as an attempt to boost tourism and gain recognition, yet the community still failed to occupy a space on many Oregon state maps. In 2004, City Manager Delphine Palmer decided it was once again time to reinvent the small city of 7,000 people.

“At that particular time, everybody in America was trying to brand their community,” said Chamber of Commerce Manager Cheryl York. “Every community was trying to figure out what their twist could be to bring tourists into the town.”

This national push to attract more tourists and increase the cash flow in small towns gained serious traction in the 1990s. Called municipal branding, the idea is meant to sell a city–and Milton-Freewater, in a state of unemployment rates double the national average at the time, needed to be sold.

In a letter to residents describing the branding strategy, Palmer stated, “We are at a crossroads where we can either move forward and try something different to increase the viability of our city, or we can sit back and watch more businesses close down while we silently say, ‘Milton-Freewater just isn’t thriving like it should, and SOMEBODY should do something!’ Now is your chance to be that SOMEBODY.”

And thrive it did. York recounted that the frogs received international attention, even earning a spot in the pages of “The New York Times.”

Though the strategy was new, the frogs were not. The city’s connection with amphibians originated 36 years ago with the first Muddy Frogwater festival; a three-day event in August which brought families together and marked the end of harvest. Based on local legend, the festival’s name originated from two boys who graffitied the Milton-Freewater official sign with the words ‘Muddy Frogwater.’ This play on words inspired York to use the image of the frog as the selling point for the town.

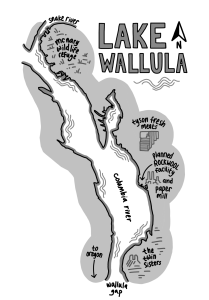

In 2004, Palmer received a grant so that any business owner could pay a small fee of 125 dollars to have a custom made wood carved frog. The physical therapist had a basketball-uniformed frog on crutches, the library had a braided frog in a pink dress reading a book. At its high point, 48 frogs could be spotted around the city, and so a map was released with the GPS coordinates of each frog.

“We gave out a ton of those maps and people loved them and thought it was a novelty,” said York. “It opened a door for conversation with anybody, everybody wanted to know: ‘We see all these frogs around town what are they for, what do they do, what’s the purpose?’ So we shared their story.”

However, not every resident from Milton was as excited about the promotional aspect of the frogs. Their opinion was that the depiction was offensive and incorrect in a city with a nonexistent population of living frogs.

“If you understand the promotional thing for a town then you realize what it does but a lot of the locals did not like it. They felt it was derogatory towards their city. And it wasn’t–it was just whimsical and fun,” said York.

Weather and time have taken a toll on the frog sculptures. The current dwindling numbers of frogs that line highway 124 leading into Oregon are indicative of the current need for a new selling point. Turning murky green and missing many webbed extremities, the wooden frogs are sure to be gone within the year.

The name of the festival is also changing to “Milton Freewater Rocks!” a development that Milton is now embracing with its growing involvement in the wine industry. Home to a growing number of vineyards, Milton received status in 2015 as a subdivision of the Walla Walla American Viticulture Area (AVA), which is now called the Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA. This rebranding of the area also marks a shift in focus to the population the town hopes to attract.

“If you’re going to market this AVA then you’re going to have to market towards someone else because you don’t really market towards the family or the kids, which is kind of sad … but this just seems like a bigger target audience,” said Watkins.

This new name allows the town to brainstorm different rocks-themed, community-organizing events: wine and cheese socials, rock walls for the kids, or community rock concerts. A movement towards the wine industry also follows suit with Walla Walla’s own branding approach, which has helped employment increase by 1.8 percent in 2014 and put Walla Walla on an internationally-acclaimed scale for its growing wine industry.

The disappearance of the frogs comes at a time of transition in Milton Freewater’s changing population and culture. Born of necessity, Watkins says the frogs were a success to be remembered fondly as a way the town garnered deserved attention.

“Change is good, it keeps things fresh. [The frogs weren’t] put out there to be a big savior to the community but they did their job to bring people, and they at least highlighted that Milton-Freewater is here.”

Carol Petersen • May 21, 2023 at 6:35 pm

Loved visiting frogs. Sorry that they are gone.