Following Food: The Story Behind Your Dining Hall Plate

The story behind what’s on your dining hall plate.

October 22, 2015

The food that many students gaze at through the windows of the dining hall three times a day is merely the tip of the vast iceberg that is Bon Appétit’s food production outfit. The process behind Bon Appétit’s food service at Whitman College is lengthy and complicated.

Each ingredient has a history of its own, and came to occupy Bon App dishes in sometimes surprising ways. Consider a potato that you might find sitting on your dinner plate. It probably came from Locati Farms, a local farm from which Whitman buys approximately 90 percent of its potatoes.

According to Executive Chef at Whitman, Jim Cooley, Bon Appétit kitchens use as much locally-grown food as they can. Whitman uses many local farms to source food, especially produce. These farms include Upper Dry Creek Ranch, Edwards Farm, Locati Farms, Cavali Acres and more. Cooley said that he tries to source as much produce locally as possible. Many students also work on these farms, including junior Mona Law.

“I wanted to work at a small, organic-style farm this past summer because I’m really interested in local and sustainable food production and I wanted to see firsthand what that looks like,” Law said in an email.

She worked on the Nothing’s Simple Farm during the past summer. Nothing’s Simple, run my Whitman ’15 alum Theo Ciszewski, is a small organic farm which provides produce to many of the high-end restaurants in Walla Walla, as well as Bon Appétit. The variety of produce grown locally is extensive, including kale, collard greens, peppers, summer squash and sweet potatoes, to name a few.

Law feels passionately about organic and local farming.

“More than just feeding people healthy food, we are defying the ecologically-destructive conventions of monocultures and chemical inputs and the rest of the whole food production chain,” Law said.

Involvement in local farming was Law’s way to influence her own food, as well as the greater community. The local farms in the Walla Walla area are one avenue for student involvement in their food.

The locally-grown potato served at Bon Appétit is now making its way to the kitchens and the cooks of the Whitman dining halls. In the dining halls, there are two sets of cooks: the morning shift and the night shift. The morning shift arrives at 5:30 a.m. to prepare breakfast and lunch. At 11:00 a.m., the night shift arrives to finish lunch and then prepare dinner. All of this preparation is done about a day in advance.

“If you don’t stay–we call it half a day ahead–if you’re not a half a day ahead and you’re doing average about 300 meals a meal period, that’s a lot of stuff to get done the day of a meal,” Cooley said.

Approximately 95 percent of the food arrives at Whitman in a raw, completely unprocessed form. If the raw potato is delivered to the kitchen on a Monday, it will be cleaned and skinned for use in a recipe that most likely won’t be served until lunch on Tuesday.

Once the chefs have prepared the food, it is served to the students (typically by other students). Bon Appétit is one of the most popular student jobs on the Whitman Campus, and is one way for students to become more involved with what they eat and with the whole Whitman community. Sydney Gilbert, first-year, works as a server in the dinning hall.

“We work pretty well together to get it all done. It’s fun,” Gilbert said. “It’s a way to interact with people.”

Student workers such as Gilbert work mostly as servers (a few are dishwashers and cashiers), yet they still have more influence over the food here than most. The student servers interact with the chefs on a daily basis and are asked for input on which recipes are received well and which are not.

The recipes used are left entirely up to the executive chefs. The potato may be served roasted in a way the chefs have never tried before–variety is important.

“We don’t have any corporate recipes, just whatever I think of. Whatever we want to do,” Cooley said.

This means that the recipes the students at Whitman are served are the result of years of observation on what the students prefer to eat, and on years of trial and error. “I follow up afterwards, I find out after dinner: Did they eat this? Did they eat that? If something doesn’t work at all the servers tell me ‘well … you might not want to do that again.'”

This trial and error is necessary because the tastes of the students are changing constantly. Within the student body are vegetarians, vegans, people with allergies and a huge number of other dietary preferences and restrictions. When planning the menu–which Jim does weekly–he must account for the season, the upcoming holidays, the weather, the current trends in food and the overall mood of the campus.

This explains why comfort foods are more prevalent during finals weeks. The complexity of judging what students will or will not eat is a challenge, which generates a good deal of waste.

“I try to balance it out so that there’s something for everyone,” Cooley said. “Sometimes the person you’re trying to take care of, or the group you’re trying to take care of isn’t very big. But they’re important. Sometimes we hit it and it works out perfectly, sometimes we run out of fried chicken and we have 500 pounds of something else left over.”

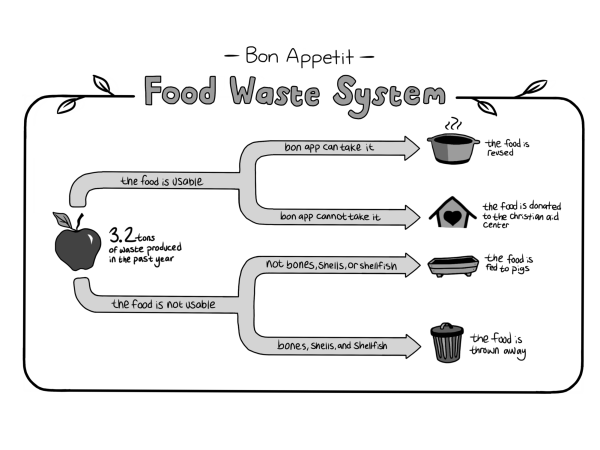

Fortunately, uneaten food doesn’t necessarily mean wasted food.

“We work really hard not to waste,” Cooley said. Anything that can be processed and made into delicious food is reused. Which means that the uneaten potatoes could make their way into a curry, or the soup for the next night.

This is an excellent method for reducing waste, but it doesn’t work for most recipes. If leftovers can be stored safely, the uneaten food is donated to the senior center to avoid wasting. The donation of leftovers is part of the corporate policy of the Bon Appétit company on a larger scale. Other branches of Bon Appétit donate food to Feed America and other local food shelters. The corporate policy of Bon Appétit also includes education about waste and healthy consumption, and batch-cooking. These help to ensure that the amount of food prepared is the amount required, and that students do not take more food than they can consume.

In past years, students negotiated food waste which is not of a quality to be served (such as produce and meat trimmings) to be sent to a local hog-farm to feed the livestock. The cooks and kitchen staff go to great lengths to make sure that food is not wasted, however the best methods all involve more involvement from the students.

“Talk to me!” Jim says. “I write the menu every week, you know, I can put something on the menu next week if someone requests it today. We’re wide open.”

The most effective way to prevent food waste is for students to communicate directly with the chefs about their needs and desires. The comment cards are one way of doing this. The chefs read the comment cards every night, and in most cases the request can be accommodated within the week. Jim also invites students to approach him personally with requests, ideas, or questions.

Incredibly simplified, the goal of the Bon Appétit food service is that the potato gets eaten, and that the students enjoy eating it. The best thing that students can do to help them with this goal is to be more aware of the work that goes in to the process of making food, and to communicate their desires for their food.

The people who work for Bon Appétit strive to be receptive to input from students, not only regarding the foods that are served but also regarding how waste is handled, and any views of students toward their food.

The chefs at Whitman rely upon the students to tell them what they enjoyed, and what missed the mark. Similarly, the peels from the potato may be wasted, or they may be sent to a hog farm on the initiative of Whitman students. The local produce eaten at Whitman may have even been grown by Whitman students. There is room for student influence at every stage in the process behind the food served here, and by understanding that process and becoming part of it, students can help to optimize the food and the community of Whitman College.

Paul Horn • Oct 26, 2015 at 3:26 pm

I thought the article was very well done. It was informative, full of facts that most of us were unaware of, and prividing answers to may of our questions.

Thanks Claire.