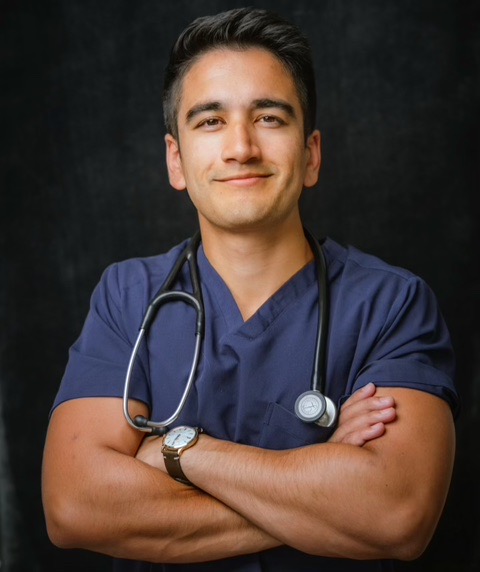

Writer and activist David James Duncan visited Whitman College last week and presented a guest lecture titled “The Wild Without, and the Wild Within: Toward a spirituality that serves the living world.” In this interview Duncan shares with The Pioneer his personal spiritual leanings and the journey that led him there.

Pioneer: What does the word “spirituality” mean to you?

David James Duncan: I’m struck by a single phrase, from the big sloppy Wikipedia entry, that spirituality is “an inner path enabling a person to discover the essence of their being.” That phrase connects with the words of Jesus, “The kingdom of heaven is within you.” This is a piece of news so incredibly good that many folks simply can’t accept it.

Heaven? In ME? Then why did I stink up the bathroom so bad this morning?!

Light a match, crack the window, and get on with it folks. Christ’s words and the Wikipedia phrase both put the responsibility for finding an inner path on us: our effort. And Christ’s words suggest our puny efforts will one day be met with a glorious answering grace.

Practicing one’s spirituality can involve religious observance and church-going, but it is not something to do once a week at church or before dinner via prayer. There is “an inner path” we can walk constantly in our day-to-day life. On such a path, intuition informs reason, the heart informs the mind, we’re all renters and an Unseen Companion is the Sole Owner, and the ordinary sometimes opens up and shows itself to be extraordinary.

Pioneer: What are your most memorable experiences, struggles or awakenings with spirituality after leaving home for the first time? How did your relationship with spirituality evolve during your late teens/early 20s?

DJD: When I was a senior in high school in the suburbs of Portland in 1969, I had an older friend down at Stanford who had become a serious seeker. He’d lost his father and I’d lost a brother. Grief opened both of us up. He was reading great literature, trying spiritual techniques and wisdom traditions on for size, and his circle of friends, though pretty wild and crazy and hippie dippie, was for the most part fueled by a yearning to live with greater compassion and love. I hitchhiked down there twice my senior year. And something passed into me. My yearning for “essence of being” grew intense.

When I graduated, I got drunk at the All Night party with my high school friends, but then went up in the Cascade Mountains and camped alone, fasting for a week by a wilderness lake. I got real lonely, real hungry, and real skinny. But my hope was to erase high school and start my life anew, based on my highest aspirations, with none of the needless presumptions and limitations that high school life inflicts on us.

And by golly, it worked. I began not just to act, but to truly feel like a different person, to experience intensified creative focus, to form new friendships and to seek and find a little spiritual solace.

Pioneer: How did you explore your spirituality during this time?

DJD: Through wisdom literature–shared with others who were passionate about it. Through spending time in the wilds. Also, shortly after I started college I befriended a young Catholic who in turn had befriended a Trappist monk who was also a novice master–a counselor to the contemplative troops, if you will. I visited the monastery with my friend in November 1970, the same monk became dear to me–and 40 years later my college friend is the novice master at the same monastery, which I still visit as often as I can.

Even more importantly, I went to India, and made contact with a way that still sustains and inspires me. I don’t talk about this publicly, but I will say that, to protect my new “inner path,” I formed a very strong bond to American wilderness, wild rivers and birds, high mountain ridgelines. I found I could keep my inner life vitally alive by spending time in wild places, listening to wordless sermons. I also gained strength from those who know and love such places. There is a very strong spiritual strain in America, running from Emerson and Thoreau and Emily Dickinson on through John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt. This strain of reverence is now, I dare say, part of a global activist movement. It has been given voice and spirit via scores of people who’ve become pen pals and personal friends–my sangha, or faith community, you could say. And many of my wilderness-loving friends are also practicing Buddhists or contemplative Christians–so religions are part of the picture. And a ragtag army of us are happy to be spiritual mutts of great passion but no particular pedigree, in the manner of, say, Muir or Mary Oliver.

Pioneer: Did you let go of any spiritual beliefs that you held strong to before then? Or, did you acquire beliefs you didn’t expect to?

DJD: Good questions! And the answer to both is: yes.

An early belief I let go of:

I held briefly to physical and dietary purity. I felt it was necessary to breed spiritual purity and clarity. I was a very pure vegetarian for half a year. I enjoyed the energy the pure diet gave me, and the sensitivity to the natural world. But when I started college I would hitch to school from my gardener’s cottage in the country, and every time a big truck would blow by it nearly gave sensitive little me a nervous breakdown! I also found that striving for physical purity made me obnoxiously judgmental toward those I perceived as impure. Some of the most soulful, well-informed, alert and compassionate people I know smell like onions or garlic or the cigar they enjoyed after lunch. Others are fishermen-and-women, and, yes, hunters too. At 18 I would have struggled to see their kindness if I could also smell their ground beef breath. But gradually it hit me: what does any of this prejudice have to do with opening up to love and compassion and the kingdom within?

I started de-emphasizing diet, kept up my other practices and pursued my passion for rivers with a fly rod in hand. Within a couple of years those fly rods became for me what a Buddhist monk’s begging bowl or Wayne Gretzky’s hockey stick or Van Gogh’s paints and brushes or Yo-Yo Ma’s cello or Harry and Hermione and Ron’s wands are to them: a magic tool that opened up a way of life, way of seeing, way of being.

A belief I didn’t expect to acquire:

I now hold that every single person is first in importance, and no one is second. Yes, some are saints, some are blackguards, brigands and SOBs, and most of us are some of both. And yes, some people, when I see them coming, make me want to run away. But there is a soul enlivening every saint and sinner. And this soul, I sense more and more strongly, is a glory in its own right–a godgiven shard of invincible perfection. The entry of this godshard into a human body is a wonder to me. Watching the births of my children made that clear forever. And I hold that this holy shard goes on shining in us no matter how many times or how deeply we bury its brilliance under untruths and cruelties and low desires and addictions and delusions. I hold that, for inconceivable reasons, it is none other than the Lord of Love Who invites all of us to live and breathe here, and now and then allows our beautiful souls to shine.